High Point:

12,430 feet on Tanima Peak

Total Ascent:

~4,500 feet

Difficulty:

Very Hard

Distance:

~16 miles

Waypoints:

40.20845, -105.56672

Route Type:

Lollipop Loop or Out and Back

Tanima Peak and the Cleaver in Wild Basin offer serious fun scrambling in Rocky Mountain National Park. Combining both peaks into a loop makes for an amazing mountain tour, though it takes a long day to reach them. There’s solid rock, lakes, and spectacular views of one of the best basins in Colorado.

Overview:

Located in the impressive and expansive Wild Basin, Tanima Peak and the Cleaver are seriously fun scrambling destinations in Rocky Mountain National Park. It’s possible to do each separately, but the loop created from combining both of them makes for a fantastic mountain tour. These peaks are deep in the Park and require a long day to reach, but if you have the weather and the time, they offer solid rock, lakes, and fantastic perspectives of one of the best mountain basins in northern Colorado.

- Tanima Peak (via the Eastern Ridge): Class 2+

- Tanima Peak (via Boulder-Grand Pass): Class 2+

- The Cleaver: Class 3+

The view to Mt. Alice from the shores of Thunder Lake.

Table of Contents:

Article Navigation: Click on any of the listed items in the table of contents below to jump to that section of the article. Similarly, clicking on any large, white section header will jump you back to the Table of Contents.

- Overview

- Scales and Criteria

- Directions to Trailhead

- Places to Stay

- Field Notes

- Journal: Tanima Peak

- Journal: The Cleaver

- Final Thoughts

- Acknowledgment

Looking down the gnarly Continental Divide. The Cleaver is the right-slanted, overhung rock in front of the massive north ridge of Isolation Peak.

Scales and Criteria:

This article utilizes three separate rating systems: Difficulty, Popularity, and a Scramble Rating indicating the hardest move or set of moves encountered. The scramble rating employs the Yosemite Decimal System. By the easiest routes, Tanima Peak is a Class 2+ hike, while the Cleaver retains a solid Class 3 rating regardless of how you scale it.

Difficulty Ratings:

- Easy: less than 5 miles, less than 500 ft. of elevation gain

- Moderate: 5-10 miles, 500-2000 ft of elevation gain

- Hard: 5-15 miles, more than 2000 ft. of elevation gain

- Very Hard: 10+ miles, more than 3,500 ft. of elevation gain

Popularity Ratings:

- Low: Large sections of trail all to yourself

- Moderate: Sizeable trail sections to yourself, crowding possible on busy summer weekends

- High: You’ll be seeing people, still a chance for solitude in spring/fall/winter.

- Very High: Almost always busy.

Scramble Rating:

- Class 1: Established hiking trail the entire length of the adventure. Low chance for injury.

- Class 2: Typically involves cross-country navigation, possibly using hands for balance but not required, steeper than Class 1.

- Class 3: Hands and feet used to scale areas, must use hands to proceed (either for balance or to help pull you up a section), increased exposure, a fall could be fatal. Helmet recommended, along with grippy hikers.

- Class 4: Climbing on very steep terrain just shy of vertical, falls could be fatal, hands employed for grip and balance continuously, ropes advisable but scalable without. Helmets are highly recommended, along with grippy hikers.

- Class 5-5.4: Near vertical and vertical climbing that involves technical rock-climbing moves, exposed, falls likely to be serious or fatal, possible to scale without ropes but only for very experienced veterans. Helmets, grippy hikers, and/or rock-climbing shoes necessary.

- Class 5.5 and up: Not covered as scrambling, full-on rock climbing with ropes, helmets, etc.

The YDS system is widely used in North America but can be quite subjective, so it is not perfect. The biggest differences I’ve encountered between Class 3 and Class 4 sections have to do with slope angle, exposure, and putting weight and pressure on hand grips (4) instead of using hands and feet interchangeably as supporting points of contact (3). It is not possible to climb a Class 4 section without using your hands to pull up some or all of your body weight. Typically, a Class 4 section will also require some type of rock-climbing move, like stemming, where hands or feet are pressed in opposition as if climbing the inside of a chimney. If downclimbing, a key difference is that most people will descend a Class 4 section facing inward, i.e., your back faces the exposure.

Always on the hunt for good scrambling on the way up Tanima Peak.

The Ultimate Offline GPS Hiking & Ski Maps

See why onX Backcountry is the ultimate GPS navigation app for your outdoor pursuits. Try Today for Free. No credit card required.

Directions to Trailhead:

This hike takes off from the main Wild Basin trailhead. It is located off of US 7, just north of Allenspark. Find US 7 and approach from either the north (Estes area) or the south (Allenspark, Lyons, Boulder, Nederland, etc.). If approaching from the south, make your way through Allenspark and look for a large brown sign for Wild Basin; there is a small left turn lane in the middle of the road. Once you see the sign, slow down, the turn is abrupt. You’ll make a hard left onto a small road and proceed past some houses and the Wild Basin Lodge. The National Park gate is located on the right side of the road and is visible when you approach.

From the north, there will be a large Wild Basin sign on your right after you pass the Meeker Park Overflow Campground. While the sign is large, there is only one so when you see it, slow down. It’ll be a right-hand turn onto a small road. Proceed until seeing the National Park gate on your right. Approach the gate and drive through to enter into Wild Basin.

Regardless of how you get to the Park gate, you’ll want to drive the dirt road into Wild Basin for its entire length until coming to a large parking lot. Make sure to follow the one-way road signs and park where able. The trail takes off from the lower loop portion.

Beautiful set of Columbine flowers, the state flower of Colorado.

Places to Stay:

Camping near Rocky Mountain National Park will cost you. The options for free area camping are limited. On a positive note, there are plenty of options, and the National Park is within driving distance of Fort Collins, Boulder, and Denver.

- Estes Park: Known as the gateway to Rocky Mountain National Park, Estes sees nearly 80% of park traffic as opposed to the much quieter western entrance near Grand Lake. The town has a ton of lodging options.

- Allenspark: A small town near Wild Basin that has a few lodging options, including the Wild Basin Lodge and the Sunshine Mountain Lodge and Cabins.

- Rocky Mountain National Park Camping

- Moraine Park Campground: $30 per site. $20 in winter. Established campground with perks, facilities, campfire grate, wood for sale in summer, and bear boxes to store food. Only loop B is open in the winter, and it’s first-come, first-serve.

- For summer, a reservation is needed quite a ways in advance to secure a spot.

- Glacier Basin Campground: $30 per site. Established campground with the same perks as Moraine Park. Reservation required.

- Backcountry Campsites: Rocky Mountain National Park has backcountry sites that you could book in advance. There is no open camping in the backcountry; it must be at designated backcountry sites. Please check the park website for more details. Backcountry sites require an overnight permit of $30.

- Camping near Estes Park

- Estes Park Campground at Mary’s Lake: Established campground, pricey $45-55. Good backup if other campgrounds are full.

- Hermit Park Open Space: $30 for a tent site, price increases if towing a trailer or for group spots.

- Estes Park Koa: Rates dependent on what you’re bringing with you but will run more than $50 a night in the busy season.

- Olive Ridge Campground in Roosevelt National Forest is the closest campground to the Lookout Mt. trail. ~$20 for a standard nonelectric site.

- Free or close to free: but a little farther (if you’re willing to drive)

- Ceran St. Vrain Trail Dispersed Camping ($1)

- County Road 47. Users have reported trash and ATV noise at this location, but it is free.

- Meeker Park Overflow Campground

Parry Primrose, defiantly growing along the final scramble to the Cleaver.

Field Notes:

Wild Basin is known for great ridgelines, beautiful lakes, expansive tundra, and looooong treed approaches. The payoff for distances covered is a larger degree of mountain solitude and 100-mile views on bluebird days. The first part of the hike to Thunder Lake is along a highway-sized stretch of trail where you can really haul. Making the lake in 2-3 hours is very doable before the sun rises; just make sure to take the Campsites Cutoff Trail to shave off a little distance. From Thunder Lake, especially if you haven’t been up there before, it helps to have some natural light to see what the path of least resistance up Tanima looks like. Once you’re on the ridgeline, navigation is pretty easy. Trekking poles are useful on the way up to Thunder Lake, but their use is limited beyond that.

Tanima Peak can be summited with some Class 2+ scrambling on great rock. Keep in mind that when you finally hit the ridgeline, you still have roughly a thousand feet of gain ahead of you. There are a handful of false summits along the way, so reserve excitement until you’re positive there’s no more ascending.

The Cleaver itself is has a healthy amount of Class 3 scrambling; there are also a set of gendarmes and ridge highpoints blocking easy passage before you get to it. You can avoid some of the gendarmes, but it will cost you some time. There is a way to ascend up and over the majority of the highpoints without more than Class 3 scrambling. If you came to scramble, it’s much more enjoyable to include the ridgelines before the Cleaver. While the scrambling is definitely serious, the exposure is fairly limited to the tops of the gendarmes and the top of a trench on the Cleaver. The final summit slabs, while steep, don’t require you to straddle the edge until you get to the summit. If you’re feeling brave, the western side of the summit is overhung and drops roughly 500 feet before meeting the slopes below.

For your weather needs, start with Allenspark’s extended forecast. The mountain forecast for Mt. Alice is a good option for the higher portions of Wild Basin. Lake Verna, while lower, is near enough to make a good third weather forecasting option. Because the approaches are long, an early start is always advised. Ideally, you want to be descending out of the alpine by 11 AM or noon latest. Snow tends to linger on Boulder-Grand Pass longer than the adjacent ridges, so if you are doing this loop in June, be prepared for some steep snow descending that may require traction devices. By early July, you can avoid the snow patch and descend a sandy slot on the north side of the pass.

The National Park has instituted a time slot system in addition to their normal entrance pass system for the summer of 2021. Do yourself a favor and take the time to understand these components by visiting the Park website. If you do not have an entrance pass or time slot, you will be turned back. The short version is that ALL visitors must have an entrance pass. If you arrive at the park (excluding Bear Lake Road) anywhere between 9 AM and 3 PM, you will also be required to produce a timed entry pass. You will be turned around if you do not have a timed entry pass. IF you have an entrance pass, AND you arrive before 9 AM, you are free to park and enjoy your day (make sure your pass is visible on your windshield), hence the “arrive early” mantra. If you exit the park between 9 AM and 3 PM, you will be required to produce a timed entry slot to reenter, or you’ll have to wait until after 3 PM to reenter.

Journal: Tanima Peak

Begin the hike from the end of Wild Basin road by following the Thunder Lake trail west. The trail is very wide and hard to lose. You’ll pass Copeland Falls after 0.3 miles. Roughly 1.4 miles into your journey, there will be a large trail junction. Staying on the main trail will bring you to Calypso Cascade and Ouzel Falls but will cost additional mileage. Instead, take a right and follow the Campsites Trail. This shortcut may not be as pretty as the main trail, but it saves time and allows you to get deeper into Wild Basin faster.

Copeland Mountain from a vantage point along the campsite spur.

Eventually, the trails rejoin; continue west, gaining elevation. Along this stretch, you’ll also pass the junction with the Lions Lake trail. Taking a right here is the easiest way to rope Mt. Alice into an adventure, but you want to continue to Thunder Lake. Click here to read our review of Mt. Alice via the Hourglass Ridge.

After nearly six miles of moderate trail walking, you’ll reach the lake and the old USFS cabin near it. If Thunder Lake is enough of an uphill effort for you, explore around the lake and make sure to visit some of the waterfalls on the way back down for an alternate day. You can read all about this variation in our trail review of Thunder Lake and the Wild Basin Waterfalls.

If you’re set on Tanima, Thunder Lake is a good place to stop and get your bearings. Tanima Peak is the long ridge to your left. You’ll want to aim for an open avalanche chute to deal with minimal bushwhacking; there are at least two options available.

Taken from in front of the USFS cabin looking south to the ridge you ultimately want to climb.

The easiest way to cross the marshy section between you and Tanima is to find the shore of the lake and proceed south alongside it. A strong social trail leads to the outflow stream, which you can cross on a log jam. Make sure to take a second and stare across the lake at the impressive views of Mt. Alice.

Looking across Thunder Lake.

Once you find either of the avalanche chutes and begin ascending, it’ll only take a few minutes for the trees to break.

The USFS cabin below as you ascend.

There are many options for climbing up the ridge. The easiest options are all Class 2 and involve talus hopping, though there is a solid rock rib running up a good portion of the ridge. This rib offers a smattering of fun Class 3 routes.

Typical terrain on the rock rib and the loose talus next to it.

I took the rib because I’ll always take solid rock over loose talus, but again, many ways up the ridge exist. Find your path of least resistance and work your way higher until you hit the ridge crest.

Gaining the crest with the moon in the background.

Once you’ve topped out on the ridge, prepare for at least another 1,000 feet of gain to reach the true summit. There will be a handful of false summits on your way to the top, but the slope angle decreases, and the rock quality is quite good. Enjoy the fantastic perspectives of Mt. Alice, Chiefs Head, Pagoda, Longs Peak, and Mount Meeker to the north.

Mt. Alice looms large over the first part of the ascent.

Turning back to the ridge, you can see the relaxed slope angle and large, blocky rock along the crest. You do not have to stay on the crest directly, but any variation will be to the south.

Looking up the ridge, the summit it not yet visible.

As you ascend, you’ll be offered a unique perspective south to Isolation Peak and the Eagles Beak below it. To either side of the Eagles Beak is Moomaw Glacier, which is composed of two pieces: a crevassed and broken eastern side spilling into an alpine tarn (Frigid Lake) and a larger component nestled into a pocked underneath Isolation Peak.

The view south to Isolation Peak, Eagles Beak and Moomaw.

The scrambling up Tanima doesn’t exceed Class 2 unless you want it to and offers relatively stable talus to hop across. Eventually, after cresting multiple highpoints by whichever way seems best, you’ll be able to finally see the summit.

The summit of Tanima.

As you approach the summit, the ridge width will narrow, and some Class 2+ scrambling will be required to reach the top. None of the moves are very difficult, but you’ll need your hands for balance and support. As is the case on many mountains in the area, you have options to make the scramble a bit harder, but it isn’t necessary.

The last push to the top. Blue=Class 2. Red=Class 3.

There is a summit register at the top; sign it if you’re interested. Otherwise, enjoy the fantastic views in all directions.

Chiefs Head, Longs Peak and Mount Meeker look quite striking from the summit of Tanima.

You can also stare down the ridge crest, which looks a lot more intimidating along its northern edge than what you just scrambled across.

Looking down the ridge from Tanima’s summit.

Tanima is a peak of contrasts. From Thunder Lake, the ridge looks serrated and intimidating. Looking west from the summit is a different scenario altogether, with healthy alpine and a gentle downward curve. There is one Class 2+ downclimb, but for the rest, descending west off the summit is a simple and enjoyable affair.

Alpine happiness. Boulder-Grand Pass is marked.

Once you start descending off of Tanima, you need to make a decision. Banking right to Boulder-Grand Pass will offer the most expedient way back to Thunder Lake. If you are set on scrambling over to the Cleaver, proceed along the southern margin of the ridge until you draw even with Isolation Peak, then turn left and scramble towards it.

Journal: The Cleaver

One of the best descriptions I’ve read about the Cleaver is from summitpost contributor Kane: “I’ll remember the Cleaver as a great place to be instead of a great summit.” So, while the Cleaver is completely dwarfed by the impressive north ridge of Isolation Peak and doesn’t have enough prominence to be its own peak, the views, scramble, and solitude really set it apart as a quality destination.

From Tanima Peak, you’ll want to descend along a healthy stretch of tundra, bearing slightly left (south) to keep Isolation Peak and Eagles Beak within sight.

Looking south to your target. Don’t be fooled by its seemingly small stature, the Cleaver radiates big mountain energy.

The Cleaver is a ridge highpoint that looks as though the top half has been sliced diagonally (as if cloven). From many viewpoints, it is either invisible or doesn’t appear prominent enough to offer any sort of alpine challenge. In fact, you won’t be able to see the Cleaver that well until you are beyond Tanima’s summit and heading towards it. Once you get close to it, though, you’ll understand why it’s a destination worth visiting.

The Class 3 scrambling is reserved for the ridgeline up to the Cleaver, so enjoy your alpine stroll until you meet the main north-south ridgeline and turn left to survey your objective.

The beginning of the ridge to the Cleaver.

There are a number of gendarmes (rock pinnacles) that look as though they will prevent easy passage. The first two workarounds are on the west side; however, nearly every gendarme can be climbed without exceeding Class 3. Climbing up and over them adds a nice scrambling component to an already fun traverse.

Rockier terrain as you break south for the Cleaver. Fifth Lake is visible to the lower right.

The descent down to the low point between Tanima and the Cleaver involves some brief Class 2 scrambling on loose and sandier rock. To your left, you can stare down the unnamed and untrailed basin that is home to Eagles Beak and a slew of alpine lakes.

Indigo Pond, Eagle Lake and Eagles Beak.

To the right, you’ll be able to stare into the ultra-scenic East Inlet Basin.

From back to front: Lake Verna, Spirit Lake, and Fourth Lake.

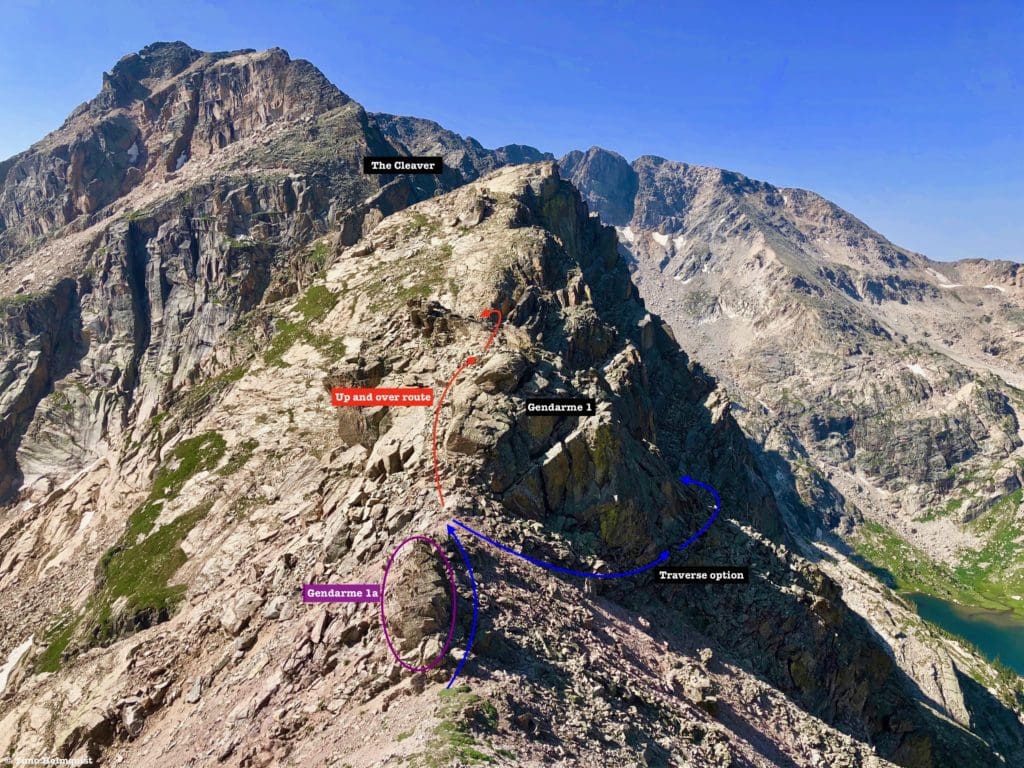

From the low point, traverse around the west side of a small pinnacle (1a), regain the crest, and run into Gendarme 1. According to various trip reports, you can traverse the western side by dropping down and circling the gendarme. This option is indeed possible but involves a quick, loose descent and some awkward traversing. For the ambitious, you can just climb over the gendarme. It looks like it won’t go, but you can descend off the back at a mid-Class 3 range with some exposure.

Options for Gendarme 1.

If you decide to go up and over, there is a section of short and loose Class 3 scrambling on sunbaked rocks to the top. The terrain steepens substantially on the other side, but a combination of sturdy rocky steps and ledges grants relatively safe passage.

Closer view of Gendarme 1 and ascent options.

By whichever you choose, you’ll end up on the other side of Gendarme 1 and in a small saddle. The Cleaver will disappear from view, only reemerging only after you pass beyond Gendarme 3.

Looking back at the various options on Gendarme 1 from Gendarme 2.

From this new saddle, you can keep left to avoid Gendarme 2. This traverse has you going on the east side of the ridge and hopping across another section of sunbaked rocks. If you want to tag Gendarme 2 (aka Stegosaurus ridge), break right and parallel the spiky rocks until finding a Class 3 gully up to the shoulder.

Gendarme 2, easily bypassed, or easily summited.

From the shoulder, a handful of small Class 3 moves will give you Gendarme 2’s summit. You can also tag Gendarme 2 from the eastern side if you double back to the summit once you pass it. Despite its small profile, the gendarme does have a bit of prominence, and you’ll descend a few feet before beginning a more substantial scramble up Gendarme 3 (aka Big Boy).

Gaining the ridge on Gendarme 3.

Like all the previous gendarmes, there are a few ways to do this. You have to climb up to the gendarme’s shoulder in most scenarios because sneaky cliffs preventing a lower eastern workaround. A western workaround is possible, but it’s a bit convoluted. The upper portion between the shoulder and the summit can be traversed but is loose and sandy where it’s not covered by alpine plants. The grippiest route is to stick close to the ridgeline and top out on or near the gendarme.

The top of Gendarme 3 with substantial western side exposure.

Whether or not you top out on Gendarme 3, take a second to admire the view south, with the Cleaver coming back into view against the intimidating north ridge of Isolation Peak. This is fantastic and gnarly terrain.

The view south from Gendarme 3.

The descent off Gendarme 3 is fairly straightforward, there is one section that will push you to traverse below the ridgeline on either the western or eastern side, but traversing is not harder than Class 2. If you are determined to stick to the ridge crest, there is a way to descend off the nose of the ridge; it just takes a little creative route finding.

The nose of Gendarme 3 with the Cleaver behind.

If you take the ridge-direct, be prepared for a few Class 3+ moves, but the rock is sturdy, and the exposure isn’t too bad.

The downclimb off of Gendarme 3’s nose.

After reaching the saddle between Gendarme 3 and the Cleaver, get ready for a stout Class 3+ scramble up an angled trench between the Cleaver and a sharp rock pinnacle. This is followed swiftly by steep Class 3 slabs all the way up to the overhung summit.

Overview of the Class 3+ trench. The red circle represents an alternative climb with decent holds.

The trench is most easily climbed right up the center. You can opt for an airy left-hand scramble or take a shot at clambering up a series of wavy rock ribs to the right if motivation strikes. The rock is generally very stable, but a few rocks at the bottom of the trench are not anchored and will move.

Looking up the angled trench from the bottom.

When you reach the top of the trench, you have to veer left and perform a few exposed Class 3+ moves to get onto the Cleaver.

Last portion of the trench, the left variation is quicker and less exposed.

The slabs are very grippy when dry and provide an exciting and excellent finish to this wonderful little peak.

The slabs with my buddy on the summit.

From the Cleaver, you have excellent views in all directions. The overhung summit to the west is particularly exciting and merits some closer inspection but be careful. It’s also hard to accurately capture the absolutely daunting ridge of Isolation Peak just south of you. There is no way to climb the ridge directly without multiple Class 5 moves. If you’re looking to combine the Cleaver with Isolation, you have to drop west roughly 200 feet, traverse, and find a gully that bypasses the ridge difficulties but still nets a Class 4 rating.

Looking south with the daunting Isolation ridge to the left.

It’s worth dropping down to Isolation’s ridge for a few reasons: to scout the workaround, to scout the Class 5 wall options, and to look back at the Cleaver for a great view of the overhung summit.

The Cleaver from under the shadow of Isolation Peak.

If you’re looking for ways to make the Cleaver more interesting than it already is, there is also a Class 4 way up it from the saddle with Isolation. Any significant variation to the right (eastern) side will knock it back down to Class 3, but if you stick with a direct climb, it’ll give you a few Class 4 moves.

Making a hard peak harder.

The brief Class 4 moves.

From the saddle with Isolation, you can traverse around the Cleaver on its eastern side, but it will require a few Class 3 moves. You can also re-ascend to the summit slabs (Class 3) and descend them back to the trench. We opted to return to the slabs since we’d already climbed them, and the route felt shorter than traversing.

Looking at the return journey challenges.

Before beginning your downclimb into the trench, see if you can spot the uber-green patches of grass on the sides of Isolation. They occupy tiny, isolated plateaus where I suspect no one has ever set foot. It’s a fantastic contrast to the rocky and rugged landscape.

Pristine green patch on the isolated sides of Isolation Peak.

Make your way back to the gentle alpine slopes on the western side of Tanima, climbing or traversing around the gendarmes as you cross them. When the ridge difficulties abate, you can successfully say you’ve conquered the Cleaver. The general order for the path of least resistance is to downclimb the trench, take a left around the nose of Gendarme 3, traverse across the right shoulder of Gendarme 3, descend to the right of Gendarme 2 to the next saddle, either climb up and over Gendarme 1 (faster but Class 3) or head west and circumvent until arriving at the last saddle, then climb back to Tanima’s western slope (Class 2).

Longs Peak and company from the alpine near Boulder-Grand Pass.

While the toughest scrambling is over, you are not anywhere near your car yet, so keep focused on the task at hand. Boulder-Grand Pass is only a Class 2 descent, but it is a rotten rock and sandy mess where things shift easily. Head to the northernmost chute descending into the pass to find a faint social trail. Careful on the descent; the sandy rock will beat up your tread and make slips a strong possibility.

Boulder Grand Pass from below.

The lake below the pass is called Lake of Many Winds, and if it’s warm enough, you can dip into the shockingly cold water for a nice energy shock. The fastest way to circle around the lake is to take a left and boulder hop along the shore until getting to a green bench on the opposite side. Continue to circumvent the lake along the green bench until a social trail becomes visible. Follow the increasingly obvious trail as it winds down towards Thunder Lake.

General path out of the alpine.

The path to Thunder Lake becomes increasingly obvious, but there’s still some distance to cover. From Lake of Many Winds, you descend into a lower alpine basin, traverse across it, hug a steep ridge, descend back to treeline, thread your way through a boulder field, descend off a rock rib, and then through a forest before arriving at the lake.

Trails exist on either side of the lake, though the fastest variation is to keep left and walk around the lake on its northern edge. Once you make it to the cabin at the eastern edge of the lake, the official Thunder Lake Trail takes over. Keep in mind; you still have 5.8 miles of descending to do before you make it to the trailhead. Pace yourself, and watch where you’re planting your feet so that you don’t twist anything on the way out.

Final Thoughts:

Tanima Peak is a fun and interesting scramble to a peak that is routinely ignored by many Wild Basin visitors. The Cleaver is a fantastic place to be along a rugged and remote stretch of the Continental Divide. Together, they make for a grand day in one of the best mountain basins in the state. The scrambling is largely on good rock, and the views are sublime on a bluebird day with stunning vistas from Thunder Lake all the way to the Cleaver and back again. Budget most of a day for this one and make sure to start early, it’s 5.8 miles to Thunder Lake, and the approach is largely forested. If you make it up here, you’re going to want to savor your time above the trees. The prime season for completing this hike with minimal to no snow is late July-September.

The Cleaver in all its glory.

Acknowledgment:

I used a variety of trip reports and guidebooks to gear up for this hike and they are listed below in alphabetical order.

A Climber’s Glossary (quoted from The High Sierra; Peaks, Passes and Trails by R.J. Secor). (n.d.) Retrieved from https://climber.org/data/glossary.html

Andy. (n.d.) Tanima Peak and Environs. Retrieved from http://www.hikingrmnp.org/2011/10/tanima-peak-and-environs.html

Foster, L. Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. (2005). Westcliffe Publishers, Inc.

Kane. (n.d.) Pilot Mountain, Tanima & The Cleaver. Retrieved from https://www.summitpost.org/pilot-mountain-tanima-the-cleaver/209195

Rossiter, R. Rocky Mountain National Park: A comprehensive Guide to Scrambles, Rock Routes, and Ice/Mixed Climbs on the High Peaks. (2015). Fixed Pin Publishing.

Popular Articles:

- Guide to the Best Hiking Trails in Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

- The Dyrt: The 10 Best Campgrounds In Colorado

- Top Adventure Sports Towns 2021: Boulder, Colorado

- Epic Adventures with the Best Guides In Colorado

- Sky Pond via Glacier Gorge Trail, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

- Scrambling Hallett Peak’s East Ridge, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

- Scrambling Mt. Alice via the Hourglass Ridge, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

- Gorge Lakes Rim Scramble, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

- Black Lake Via Glacier Gorge Trail, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

- Scrambling To The Lake Of The Clouds, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

Enroll With Global Rescue Prior To Embarking On Your Next Adventure.

When a travel emergency arises, traditional travel insurance may not come to your aid, and a medical evacuation can cost up to $300,000.

The cost when you have a Global Rescue membership? $0. That’s why when the unexpected happens, you want the leader in rescue, evacuation and medical advisory behind you. You want Global Rescue.

Terms of Use:

As with each guide published on SKYBLUEOVERLAND.com, should you choose to this route, do so at your own risk. Prior to setting out check current local weather, conditions, and land/road closures. While taking a trail, obey all public and private land use restrictions and rules, carry proper safety and navigational equipment, and of course, follow the #leavenotrace guidelines. The information found herein is simply a planning resource to be used as a point of inspiration in conjunction with your own due-diligence. In spite of the fact that this route, associated GPS track (GPX and maps), and all route guidelines were prepared under diligent research by the specified contributor and/or contributors, the accuracy of such and judgement of the author is not guaranteed. SKYBLUE OVERLAND LLC, its partners, associates, and contributors are in no way liable for personal injury, damage to personal property, or any other such situation that might happen to individuals following this route.