|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This is the third of four articles about skiing in Rocky Mountain National Park’s famous backcountry lines. We’ll focus on the Longs Peak region, which offers a variety of intermediate and challenging options for skiers east of the Continental Divide.

Overview

This is the third of four articles dedicated to skiing the more famous backcountry lines in Rocky Mountain National Park. We’ll take a look at the Park in general before zeroing in on the Longs Peak region. For those looking for a variety of intermediate ski lines or options for some of the toughest lines east of the Continental Divide, the Longs Peak region is your Rocky Mountain go-to.

Backcountry Skiing comes chock full of benefits and risks, almost in equal measure. It is a discipline that rewards methodical and purposeful learning with a deeper connection to nature. It can also be very dangerous for the uninitiated and seasoned veterans alike; avalanches don’t pick favorites. However, by arming yourself with the right gear and planning knowledge, backcountry skiing can satisfy the outdoor itch for multiple lifetimes.

It can be noted that this guide includes 3D interactive maps of each region described. Each ski line and their access routes are shown for convenience.

Warning: This is part of a four-part series on backcountry skiing in Rocky Mountain National Park and only encompasses a brief overview available ski lines in the Longs Peak Region. For tips and best practices for planning a backcountry skiing adventure, please refer to our Backcountry Ski Planner. For ANYONE traveling into avalanche territory, consider enrolling in an Avalanche training course by AIARE; it absolutely save lives.

Mountain guide, Joey Thompson, climbing the north face of Longs Peak in Rocky Mountain National Park just before skiing it. Photo by Rob Coppolillo

Support Skyblue Overland™ on Patreon!

If you’d like to support our efforts for a few dollars a month, please subscribe to our Patreon page. Every donation energizes our team to keep writing detailed trail reviews, gear reviews and adventure guides. Thank you!

Table of Contents:

Article Navigation: Click on any of the listed items in the table of contents below to jump to that section of the article. Similarly, clicking on any large, white section header will jump you back to the Table of Contents.

- Overview

- Backcountry Gear

- Backcountry Planning

- Rocky Mountain National Park Overview

- Longs Peak Area Overview

- Access

- Places to Stay

- Our Rating System

- Battle Mountain

- Longs Peak North

- Longs Peak South

- Quick Terminology Reference Guide

- Final Thoughts

- Additional Resources

Backcountry Gear

Before we begin, let’s lay out some quick backcountry gear knowledge (for a more comprehensive guide, check out our article, Backcountry Gear: Essentials for Human Powered Skiing). The list below is crucial, don’t skimp on gear when avalanches are in play.

- Skis/Helmet/Gloves/Goggles

- Winter Clothing: waterproof shells, thick ski socks, layers, puffy, beanie, hand warmers, etc.

- Skins

- AT Bindings (Frame or Tech)

- Avalanche Gear: Beacon, Shovel, Probe, and Radio

- Backcountry ski pack

- Food/Water/First-Aid Kit

- For multi-day adventures: 4-season tent, winter rated sleeping bag, avalanche airbag, orienteering equipment, batteries/rechargeable batteries

- Mountaineering Axe and Crampons. While there are hundreds of lines that do not require these tools, some of the most epic lines in Rocky Mountain National Park do. Research which crampons fit over your alpine or tech boots before buying! Generally speaking, you do not need an “Ice” axe unless you are climbing an ice wall, a mountaineering axe should work fine for most couloirs. However, some of the hardest ski mountaineering routes in the area demand more. Analyze your skill level and the route of choice BEFORE settling on gear choices.

Remember, it isn’t enough to simply own gear; take the time to figure out how to use it before heading out. Speed is key, especially in a backcountry avalanche rescue. Visit Backcountry Gear: Essential for Human Powered Skiing to get comfortable with the necessary gear and how to use it.

Backcountry Planning

Once you have the gear and know how to use it, it’s time to start planning. We’ll briefly break down the central components below, but check out our Guide to Planning a Backcountry Ski Adventure for an in-depth analysis of the planning process. A good plan can separate success from disaster. No outdoor activity is worth your life.

Pre-Planning: Learn how to Ski at an EXPERT level before heading outside ski resort boundaries. Find a squad. Start backcountry gear research. Hone your craft. Get in shape.

Long-Term Planning

- Geographic reduction: where are you skiing? Start big, get small.

- Weather and snowpack research.

- Research ski lines using books, online resources, and forums. Key data:

- Total distance, total climb, total descent, slope angle

- Local Emergency contacts

- Unique factors: trees, cornices, couloirs, avalanche history

- Get into the maps and apps, know the area like the back of your hand.

Short-Term

- Managing Expectations

- Constantly check weather updates until the morning you leave. Remember, snow reflects light, if it’s a sunny day, bring sunscreen!

- Popularity of your backcountry line.

- Tell people where you’re going and who to call if things go wrong.

- Have a back-up plan.

- Who’s got the medical training?

- Go over the plan in detail with your squad. CHECK FOR UNDERSTANDING.

- Packing

- Make sure everything fits, and you can access your avalanche gear quickly. Time is critical in a burial situation.

On-site Planning

- What do you see when you get there? Watch out for tree-wells, wind-loaded slopes, cornices, bergschrunds, and other topographical considerations.

- Timing and snow surface i.e. environmental factors. Not all snow skis the same.

Post-Planning

- Analyze: What worked well? What didn’t?

- Ease into the harder stuff.

The steps listed above are only a skeleton outline; see our Guide to Planning a Backcountry Ski Adventure to iron out the critical details. Remember, you can always take an avalanche safety course through AIARE; it can absolutely save lives.

Guided Backcountry Skiing adventures in Rocky Mountain National Park

A privately guided ski tour is the perfect chance to dive into Colorado’s revered backcountry— without the cost of a lift ticket or back-to-back traffic along the usual routes.

Rocky Mountain National Park Overview

Rocky Mountain National Park Entrance at Beaver Meadows near Estes Park, Colorado.

Rocky Mountain National Park is the third most popular National Park in terms of visitation, right behind The Great Smokey Mountains and the Grand Canyon (nps.gov, 2020). A lot of its popularity has to do with the relative ease of access (Denver and its major international airport are less than two hours away) and dramatic glaciated terrain, which creates stunning vistas along the Continental Divide. The other winning ingredient is backcountry skiing.

While winter is a down season in terms of Park visitation, Rocky Mountain supplies some of the best winter and spring skiing in northern Colorado. Most of it is easily accessible from the more trafficked eastern side of the park. Please see our Hidden Valley/Sundance Mountain article for detailed information on a great backcountry introductory area. If variety is your game, check out our Bear Lake Area article, containing some of the highest concentrations of ski lines in the park. If, however, your sights are set on other areas, have no fear; with Rocky Mountain National Park clocking in at over 415 square miles, it’s easy to find new and exciting places to recreate.

Because it is a National Park, there are many options for weather forecasting. During the planning phase of any backcountry ski trip, it’s important to check the weather using multiple sources. The forecast for Estes Park is a good starting point. Estes sits right outside the eastern park boundary, only thirty minutes from Longs Peak. There is also a forecasting station at the Alpine Center off of Trail Ridge. Between the forecasts for Estes and the Alpine center, you can usually lock in a good spectrum of possible weather factors. In addition, the mountain weather forecast for Longs Peak is very handy and comes chock full of weather details reported from three different elevation gradients. Mountain forecasts for neighboring Mt. Meeker and Storm Peak keep the forecast details flowing.

Keep in mind: there are multiple components to the weather; it’s not just about precipitation. The temperature will dictate what layers to bring, and local weather patterns will help you figure out what’s important. For example, in Rocky Mountain and the larger Front Range in general, make sure to check the wind forecast. The Front Range is notorious for strong, blustery winds, and fighting your way up to a ski line in 50mph gusts is not fun.

There are also Snotel weather station sites scattered throughout the backcountry offering snowpack data. It can be a bit confusing to sort through the site, but here is the interactive map option. Use the menu on the right-hand side to create specific condition queries. The linked map will open with a window to the specific station at Bear Lake. Snowpack data is really important for backcountry skiing; not only will it tell you if there is even enough snow to ski on, but it will also show you whether or not the area is experiencing an average winter. Any significant deviation away from average is noteworthy. Deep winters create more pronounced avalanche conditions, but wimpy winters can as well, especially if a storm overloads weak and unstable snow. Snowpack science should be a critical component of planning.

As crucial as snowpack data is, the numbers would be incomplete without an avalanche forecast. This forecast is MANDATORY before heading out. In Colorado, we are lucky to have the CAIC (Colorado Avalanche Information Center). The information is easy to read, the maps are color-coded, and a flurry of explanations gives depth to the forecast. More specifically, Rocky Mountain is in the Front Range Zone; make sure you are checking the right area for the most accurate information. Do not go into the Colorado backcountry without checking CAIC.

Global Rescue is there whether you’re hiking, kayaking, snowmobiling, fishing or simply enjoying the outdoors and get ill or injured and you’re unable to get to safety on your own. Global Rescue is the red button you push in an emergency. Their team of medical and security experts come through for you when it matters most.

Longs Peak Area Overview

Map of Longs Peak Area.

Longs Peak is a gargantuan and highly visible 14,259-foot mountain. Longs is not only the highest mountain in the National Park; it is the only 14,000-foot mountain within 40 miles. Outside the Longs Peak massif (which includes Mt. Meeker), no other mountain in the Park comes within 650 feet of its height, giving the mountain a huge visible prominence. It is such a dramatic peak that on bluebird days you can see it from Denver International Airport. Famous for its inclusion in the 14,000-foot club, Longs has been a mountaineering destination for hundreds of years and has become a challenging ski destination for dedicated winter professionals.

Like Bear Lake to the north, Longs Peak is very well documented and many of its ski lines are challenging mountaineering routes as well. Unlike Bear Lake, the access options are more varied. There are at least three ways to approach the ski lines here, each offering a different experience. Far and away the most popular approach is from the east, starting at the East Longs Peak Trailhead. This approach provides access to Battle Mountain, Longs Peak’s north face, and the Chasm Lake area. From the south, dedicated backcountry skiers can utilize Wild Basin’s Sandbeach Lake Trail to get to epic lines such as Keplinger’s and Dragon Egg Couloirs. The final approach actually starts from the Bear Lake area to the north and takes you into the always stunning Glacier Gorge before connecting with the Trough Couloir. However you choose to approach the area, adventure awaits.

Keep in mind: if this is your first-time backcountry skiing in Rocky Mountain National Park, it may be worth checking out Hidden Valley and Sundance Mountain before diving into the Longs Peak Region. The lines around Longs Peak are all Intermediate and above, with a few reaching the highest designation we have (Very Difficult). While many lines feature excellent vertical descents, some have pronounced avalanche risk, and everyone needs to have the appropriate gear.

Access

There are three main ways to get into the Longs Peak backcountry area in the winter. The obvious first choice is the East Longs Peak Trailhead. This parking area is located off of US 7, roughly 20 minutes south of Estes Park. The road to the trailhead is plowed in the winter but is a much lower priority than Bear Lake Road; after a large storm, it may take a little time for access to open up.

The second most popular way is to park along Bear Lake Road at the Glacier Gorge Parking area and skin south. Bear Lake is a high-priority area and is consistently plowed. While parking shouldn’t be an issue deep in the winter, once spring weather rolls in (April and onwards), the popularity of the area absolutely explodes. Arrive early and preferably on weekdays. If you arrive and all parking is full, try the Bear Lake Parking lot at the end of the road (~9.4 miles from the start of the road and ~10.5 miles from the Beaver Lake Meadows Park entrance). In mid to late May, another option opens up. If both lots are full, you can head down to the Park and Ride lot near Glacier Gorge Campground and take a free shuttle to the trailhead. The shuttle service is seasonal; check the park website here to find out when the shuttle opens.

The third and longest approach option is via Sandbeach Lake Trail in Wild Basin. This trailhead is also reached via US7, just north of Allenspark and about 30 minutes south of Estes Park. Wild Basin is appropriately named; this approach is a true wilderness adventure. After following a fairly well-established skin track for the first half, you’ll need to veer north into trail-less backcountry to reach Keplinger’s and Dragon’s Egg Couloirs. Only take this approach if you’ve scouted the route before and have extensive backcountry experience in all four seasons.

Remember, an entrance pass is required to visit Rocky Mountain National Park. These passes can be purchased online. Please visit the official National Park website to ascertain what passes and entrance fees are required. Fines will be administered to those without proper passes.

Places to Stay

A cool winter night in Estes Park, Colorado.

The best option for accommodations near Longs Peak is Estes Park. The town is a four-season playground offering myriad lodging opportunities. It is impractical to stay in Grand Lake on the western side of the park because of seasonal closures along Trail Ridge.

If you’re based in the Front Range, Longs Peak is only an hour and a half from Boulder and metro Denver. Loveland, the closest major town to Estes Park, is only 45 minutes away with no traffic. Due to the relative proximity of Longs Peak to major population centers, it may be easier to day-trip up to the ski area.

If you want to stay in Estes, please visit the tourism bureau website here. The search filters on the site will help you narrow down options. Additionally, Airbnb frequently offers great options. Because winter is a down season in terms of visitation, many lodging establishments will be offering discounts and perks to attract clients.

Our Rating System

Below you’ll find route descriptions, maps, and ratings as they pertain to the lines we cover. These articles cover the most reported and referenced lines, not all possible lines you could ski. We utilize a four-tier rating system illustrated as follows:

-

Beginner (Green)

-

Intermediate (Blue)

-

Difficult (Maroon)

-

Very Difficult (Black)

Some areas covered only exhibit a few tiers; others exhibit all of them. Regardless, it is important to understand that each rating does not ONLY correspond to the steepest slope angle skied. Some lower-angle Difficult terrain is simply difficult to access and requires an immense amount of effort to attain, hence the harder rating. Take the ratings seriously as the separation between Difficult and Very Difficult often involves many of the hallmarks of true ski mountaineering, ropes, legitimate ice axes, mountaineering crampons, etc. It is incumbent upon each reader to understand their limits. Always start small.

Battle Mountain

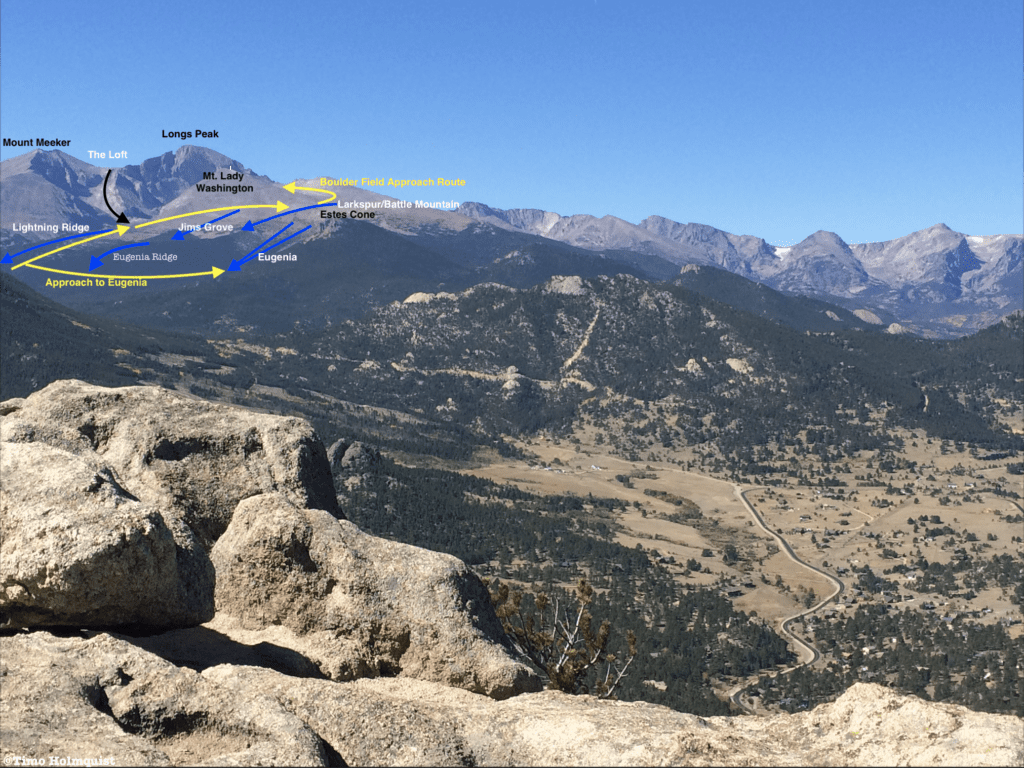

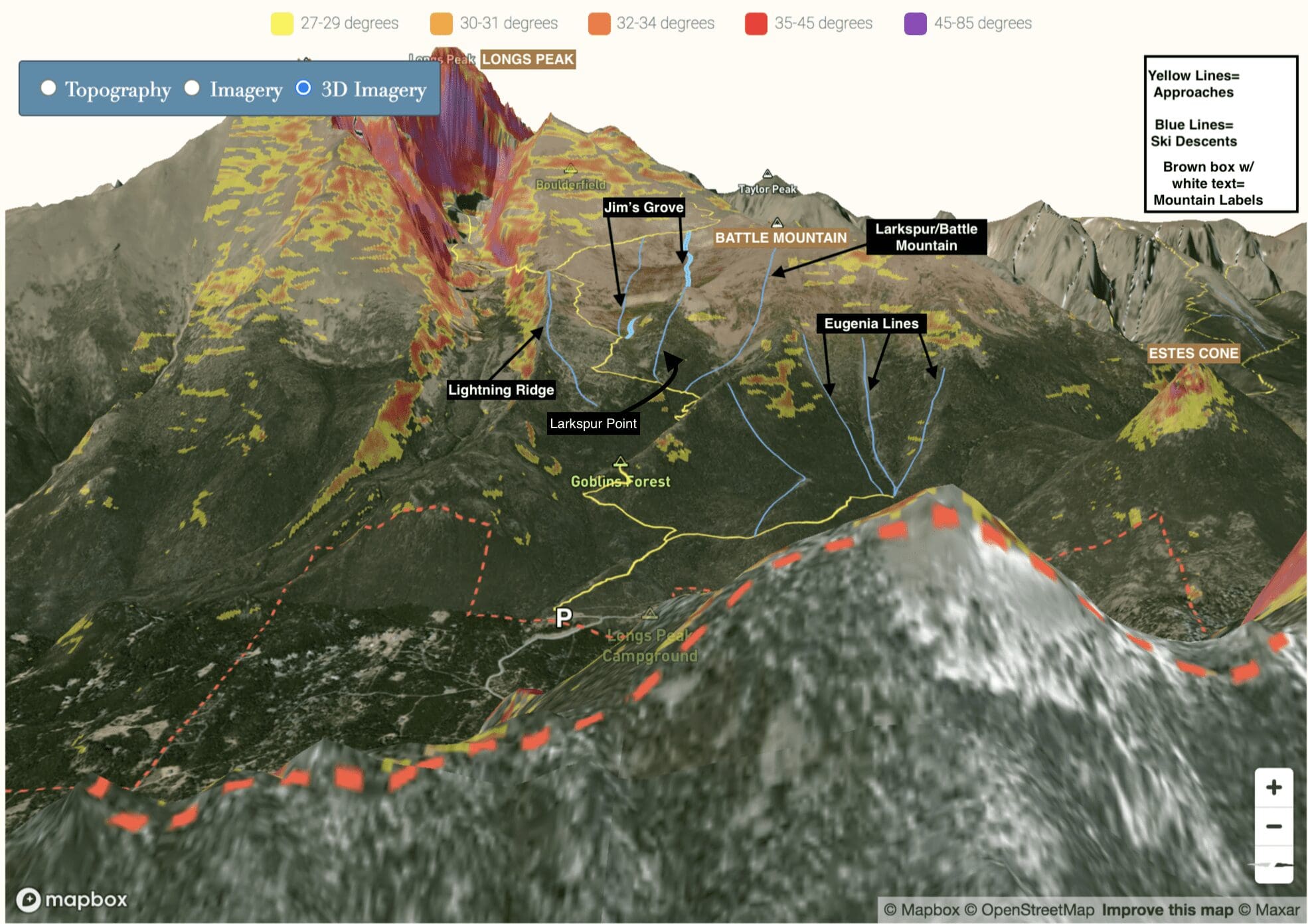

Map of Battle Mountain area including Lightning Ridge, Jim’s Grove, all Eugenia Lines and Larkspur/Battle Mountain Lines.

Ascent Routes

This approach route makes use of the popular East Longs Peak Trailhead. You’ll park at the upper lot (if parking is available) and skin up the East Longs Peak Trail (the standard summer route up Longs). The trail is very well-traveled and difficult to lose, even in the winter.

The Eugenia Break

About 0.5 miles into your journey, you’ll arrive at a junction. Take a right to get to the Eugenia area. Eugenia was an old mining location before the National Park designation, and remnants of mining equipment are visible here in the summer. Traverse north, maintaining your elevation when able, and snagging glimpses of Estes Cone through the trees in front of you. You’ll have a few different options to ski from this area with the Eugenia skin track offering access to the bottom of the lines. These lines are generally low angle and fun mid-late winter, avalanche conditions permitting. Since they face east, try to hit the runs early so as to avoid late winter and spring melting.

Photo of the Longs Peak area ski lines from Kruger Rock.

Eugenia Ridge

-

Essentials: 0.67 miles, 985-foot vertical

-

Status: Intermediate

-

Steepest Slope Angle: 20-25 degrees

-

Great for: Low angle tree skiing, laps.

Accessed via: East Longs Peak Trail, take a right at Eugenia Trail Junction. Less than a half-mile later, the line takes off to the left (west), before curving to the south. It may be hard to identify without scouting the route ahead of time. An alternative solution is to take the easier distinguishable Eugenia main ascent and skirt the ridge south until reaching the start.

Eugenia (Main)

- Essentials: 0.75 miles, 1117-foot vertical

- Status: Intermediate

- Steepest Slope Angle: 25 degrees

- Great for: Low-angle laps in a sheltered area, a mixed bag of lower alpine and tree skiing.

- Accessed via: East Longs Peak Trail, take a right a half-mile in at the Eugenia Junction and proceed north for another 0.84 miles until reaching an obvious stream called Inn Brook. The summer trail continues north to Estes Cone. To ski Eugenia, break left and follow the drainage uphill. You’ll pass through an old slide path on the way to the alpine. Maintain the trajectory of the drainage, skinning up as high as possible with the available snow coverage. Drop in when desired.

North Variation: Intermediate. Climb up the slide path to the start of Eugenia and strap in. After you turn around to descend, sight the ridge (skiers left) that outlines the northern edge of the Inn Brook drainage; Estes Cone will dominate the view behind it. Thread your way down the ridge crest, eventually spilling right towards where the approach trail crosses the creek.

At A Glance: 0.56 miles, 911-foot vertical, steepest slope angle: 25 degrees.

South Variation: Intermediate. Climb up the slide path to the start of Eugenia and strap in. After you turn around to descend, look to your right and pick a line tangential to the main Eugenia descent. A mix of low alpine and mixed trees offers fun skiing in good conditions. Because you are on the near side of the creek, pay special attention to when the approach trail intersects your path or veer left into the main drainage to more easily sight the connection.

At A Glance: 0.75 miles, 1144-foot vertical, steepest Slope Angle: 25 degrees.

Jim’s Grove to Battle Mountain

At the intersection with the Eugenia trail (0.5 miles from East Longs trailhead), continue straight, heading for the Goblins Forest Campsite area. After passing Goblins Forest, the trail will parallel Alpine Brook heading north. A few points of a mile later, the trail will cross Larkspur Creek (which comes down from a slope to the right). A few dozen yards BEFORE this spot is the bottom of Larkspur run. Turn right and begin climbing north-northwest up the ridge to attain the line.

If continuing on East Longs Peak Trail, you will cross Larkspur Creek. The trail will turn south after a couple of switchbacks and some elevation gain. Once you begin heading south, look to your right for an opening in the trees. When attained, begin skinning up the slope (west) to access the Battle Mountain/Larkspur line.

Passed this point, the main trail will cross Alpine Brook on a footbridge (still heading south). Taking a right before the crossing and peel away to climb a ridge north of the drainage. This climb will take you to the top of the Larkspur Point Line.

If none of those options excite, continue on the main trail as it crosses Alpine Brook and enters a sparsely vegetated slope. The alpine begins to present itself here. The trail will eventually angle back to Alpine Brook at the Battle Mountain Group Campsite. From here (if ample snow is available), you can head directly west to skin up the main route of Jim’s Grove. If you’d rather stick with the trail, no problem, it’ll zig zag you into the alpine, passing the junction for Chasm Lake (where access to the Lightning Ridge Line is). Stay on the trail to Granite Pass. As you begin traversing north across the flank of Mount Lady Washington, scout descent lines to your right and peel off to begin Jim’s Grove descent.

Photo of the Longs Peak Area Ski Lines including Lightning Ridge, Jim’s Grove, Battle Mountain and the Eugenia Lines.. Notice that the slope angles are color coded. 3D Rendering by Skyblue Overland.

Larkspur/Battle Mountain

- Essentials: 1.02 miles, 1400-foot vertical

- Status: Intermediate

- Steepest Slope Angle: 25 degrees

- Great for: Low alpine and mix veg laps in a beautiful setting.

- Accessed via: East Longs Peak trail passed Goblin’s Forest Campsite. Pay attention to creek crossings and orientation of the trail. To access this main route, the trail will cross Larkspur Creek first, go over a couple of switchbacks and then head abruptly south. The end of the line spills into the trail from the right in this section. If you cross Alpine Brook (still heading south) you’ve gone too far.

Larkspur Variation: After Goblin’s Forest on the East Longs Peak Trail, pay attention. BEFORE you cross Larkspur Creek, peel off into the woods to the right of the trail. Skin up the ridge in a north-northwest orientation to avoid steeper areas to the east. Once on the ridge crest, turn and burn, or descend north off the opposite side to reach the top of some of the main Eugenia lines.

At A Glance: 0.33 miles, 586-foot vertical, steepest Slope Angle: 25 degrees

Larkspur Point Variation: Before crossing Alpine Brook on the footbridge, peel off into woods following the creek briefly and then ascending through the trees to the west until breaking treeline (this will be an ascending traverse). A slightly longer but easily navigable alternative is to keep to the main trail until reaching signs for Battle Mountain Groupsite. Leave the trail here and make your way northwest, skirting steeper sections as you go. Past treeline, find you start and ski east back to the Alpine Brook drainage.

At A Glance: 0.41 miles, 821-foot vertical, steepest Slope Angle: 27 degrees

Jim’s Grove

- Essentials: 1.09 miles, ~1000 foot-vertical

- Status: Intermediate

- Steepest Slope Angle: 25 degrees

- Good for: Low-angle alpine laps in a beautiful setting. Late winter-early spring ideal as the east-facing runs here don’t hold snow as long as others.

- Accessed via: East Longs Peak trail to Battle Mountain Groupsite. From here, you can skin directly west up the drainage before intercepting the top of the line on the shoulder of Mount Lady Washington. Or, continue up the main trail passed Chasm Lake junction, continuing up towards Granite Pass. When the trail begins its ascending traverse to the north, pick your descent line to your right back down the drainage. A lot of the shallow basin is skiable in the right conditions, have at it.

Lightning Ridge

- Essentials: 1.01 miles, 1075-foot vertical

- Status: Intermediate

- Steepest Slope Angle: 25 degrees

- Good for: Low angle alpine laps, close enough to East Longs Peak Trail to provide logical bailout option. DO NOT take this ridge down too far or the slope angle increases, trees thicken, and the chance of getting lost increases.

- Accessed via: East Longs Peak Trail to Chasm Lake Trail Junction. At the junction, turn left until you’re looking down the ridge crest (east). From this viewpoint, Longs Peak should be behind you. Hop to the ridge top and pick your line, staying close to and left of the ridgeline. A right-hand descent leads to cliffed out and bushwhack terrain. Descend the open ridge at a leisurely pace and veer left to reconnect with the ascent approach. If going for a longer descent, continue down the ridge (east) until the terrain steepens, or you hit treeline, then turn and skin up to reconnect with the East Longs Peak Trail.

Longs Peak North

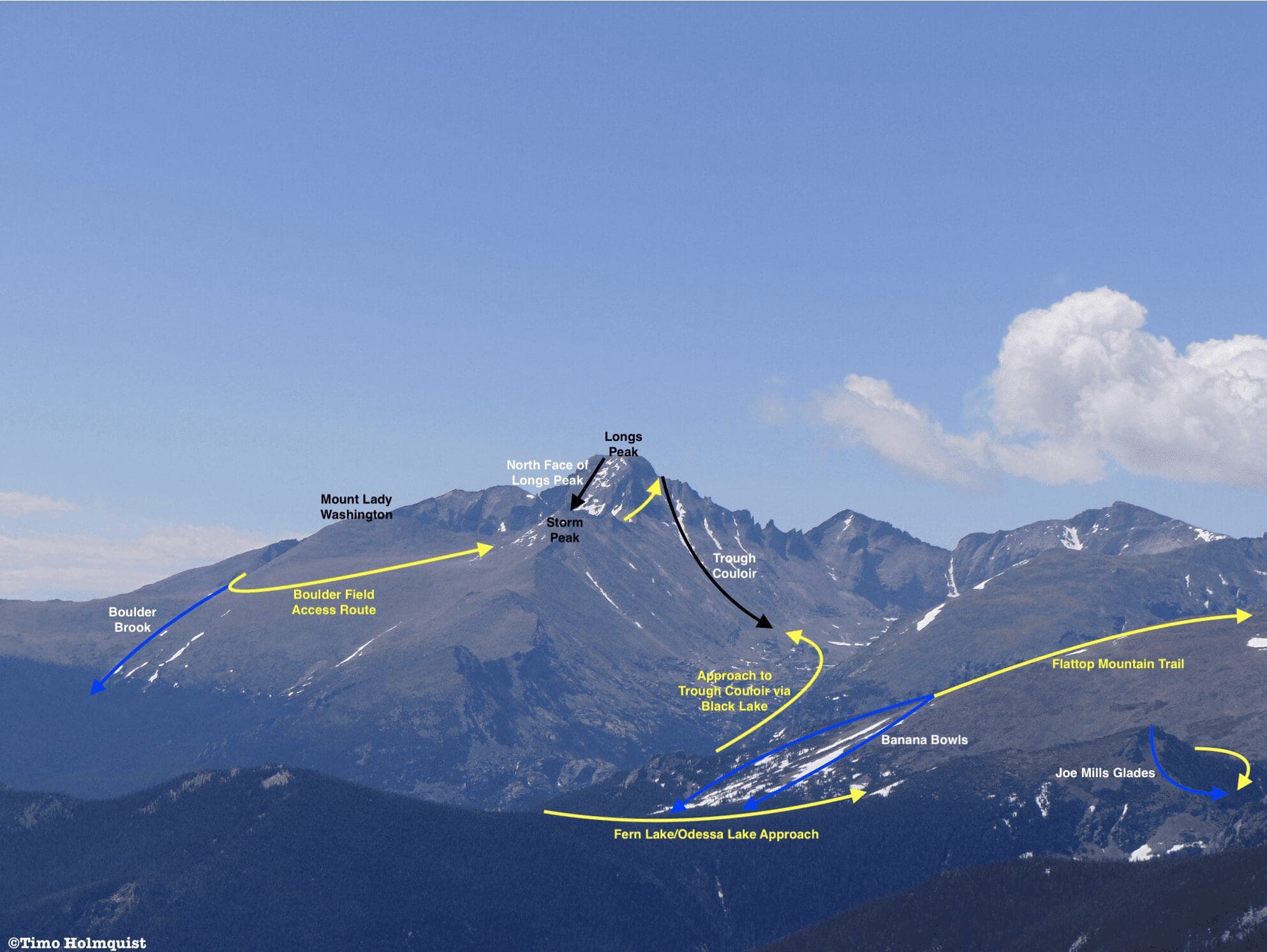

Map of Longs Peak North Area including Boulder Brook, North Face and Trough Couloir.

Ascent Routes

Lines off of the north side of Longs Peak can be accessed from a couple of different routes. The most popular would be East Longs Peak Trailhead. If you travel beyond the lines on Battle Mountain and over Granite Pass, you’ll be able to get at the Boulder Brook descent. A continued ascent into the Boulder Field will allow you to spy the North Face descent line (aka Cables Route). Be warned: this approach is over 5 miles one way. Alternatively, once you make your way to the Chasm Lake Trail junction, take a left and proceed into the Chasm Lake area for access to The Loft and Lambslide Couloir. If approaching from Bear Lake, you can take the Glacier Gorge ascent route south beyond Black Lake for 3.3 miles (one way) to access the bottom of the Trough Couloir.

Every one of these approach routes ends in the alpine where protection from the elements is minimal; plan accordingly.

Boulder Brook

hoto of the Longs Peak Area Ski Lines as seen from Trail Ridge Road looking south.

- Essentials: 0.66 miles, 1185-foot vertical

- Status: Intermediate

- Steepest Slope Angle: 27 degrees

- Good for: Alpine laps in a wide-open bowl, intermediate skiers looking for experience. Also great for a workout due to the ~4.75-mile approach.

- Accessed via: Jim’s Grove ascent route (aka East Longs Peak Trail). Take this well-traveled approach above treeline and passed Chasm Junction. Above Chasm Junction, the trail will ascend north alongside the flank of Mount Lady Washington. Once you reach Granite Pass (ascending above the lines for the Jim’s Grove), you’ll be given your first views of the wide-open bowl around Boulder Brook. Choose your descent line and ski down to the trees. Reclimb to the ascent route for your exit.

Photo of the North Face of Longs Peak from the Boulder Field.

Photo of the North Face of Longs Peak from the Boulder Field. Photo by Timo Holmquist.

North Face of Longs Peak

- Essentials: 0.26 miles, 975-foot vertical

- Status: Very Difficult

- Steepest Slope Angle: 50 degrees

- Good For: A true mountaineering and skiing experience, only for veterans with coherent backcountry skills and lots of experience. Crampons and ice axe are a must for possible ice bands. Not for beginners. Note: This line only has enough snow to cover the crux after a series of strong spring storms; otherwise, you will be downclimbing. If downclimbing the crux, ropes and gear are highly recommended.

- Accessed via: Jim’s Grove ascent (aka East Longs Peak Trail) up to Boulder Brook. When you pass the Boulder Brook line, start heading south along its upper reaches until you reach the Boulder field, a high elevation flat area with the North Face of Longs Peak prominently featured. Scout your line from here, it descends from the top of Longs down the left side of the North Face towards you. There are two options; either climb up the descent route (in the summer, this route is rated as a 5.4 and called the Cables route) or wrap around the summit via the Keyhole ascent route until topping out on Longs. In either scenario, this is a massive day.

Trough Couloir

Photo looking down the Trough Couloir when I first climbed Longs, but there isn’t much snow. There is a view of Black Lake in Glacier Gorge in the valley below.

Photo looking down the Trough Couloir when I first climbed Longs, but there isn’t much snow. There is a view of Black Lake in Glacier Gorge in the valley below. Photo by Timo Holmquist.

- Essentials: 0.78 miles, 2463-foot vertical

- Status: Very Difficult

- Steepest Slope Angle: 45 degrees

- Good for: A long but fairly consistent ski line netting nearly 2500 feet. For experienced backcountry skiers only, crampons and axe required. Not for beginners. Extreme avalanche danger mid-winter.

- Accessed via: There is no easy way to reach this line. The shortest way to access the couloir is via the Glacier Gorge Trailhead off of Bear Lake road. Skin south through the scenic Glacier Gorge, passing Black Lake until arriving at the couloirs exit. The approach, while shorter, involves more than four miles of skinning and climbing with a thigh crunching 4,129 feet of gain, 2500 feet of which occur within the last mile. The longer but more mellow, East Longs Peak Trailhead approach will ferry you to the Boulder Field, through the Keyhole, and force a traverse of the ledges until reaching the upper part of the couloir. From there, climb as high up the couloir as you’re willing to go, strap in and ski down. This approach will cost you ~4400 feet to the top of the couloir over 6.58 miles.

Map of Chasm Lake Area including The Loft and Lambslide Couloir area.

Photo of Chasm Lake to The Loft and Lambslide Area.

Lambslide Couloir

- Essentials: 0.32 miles, 1186-foot vertical

- Status: Difficult

- Steepest Slope Angle: 45 degrees

- Good for: Loft alternative and slightly less difficult than North Longs or Trough Couloir. This is a dangerous and avalanche-prone area; proceed with caution. NOT for beginners.

- Accessed via: East Longs Peak Trail and Chasm Lake trail. ~5 miles and 2400-foot climb to Chasm Lake. It takes another 1651 feet to climb to the top of the couloir. This couloir holds snow deep into the summer and can provide a stellar June descent. Watch for afternoon melting; avalanche and rockfall danger is high. The couloir makes for a tamer descent than the Loft and slices through a truly spectacular area. A classic descent in the right conditions.

The Loft

- Essentials: 0.8 miles, 1834-foot vertical

- Status: Very Difficult

- Steepest Slope Angle: 50 degrees at the headwall

- Good for: If heading above the cliff bands to the actual Loft, this is a challenging and dangerous alternative to popular routes nearby. Expert/professional winter recreationists are best suited to handle the top of this route where crampons and ice axes are required.

- Accessed via: ~4.15 miles and +2200 feet to couloir bottom. Best approached from the bottom to sight possible hazards and think about best lines of descent. The headwall on the Loft is what sends it over the edge in terms of difficulty. There is a ledge to climbers left that many use to help pass the difficulties.

Lower Variation: Difficult. This variation only requires you to ascend as high as you’re willing to go. The headwall climb of the Loft is abrupt and obvious to see. Without climbing the crux, you still net more than a thousand feet of descent and can combine with Lambslide for a less extreme day. As always, avalanche gear is a must, along with a helmet for rockfall potential.

At A Glance: ~0.5-0.6 miles, ~1275 foot-vertical

Steepest Slope Angle: 35 degrees (brief)

Longs Peak South

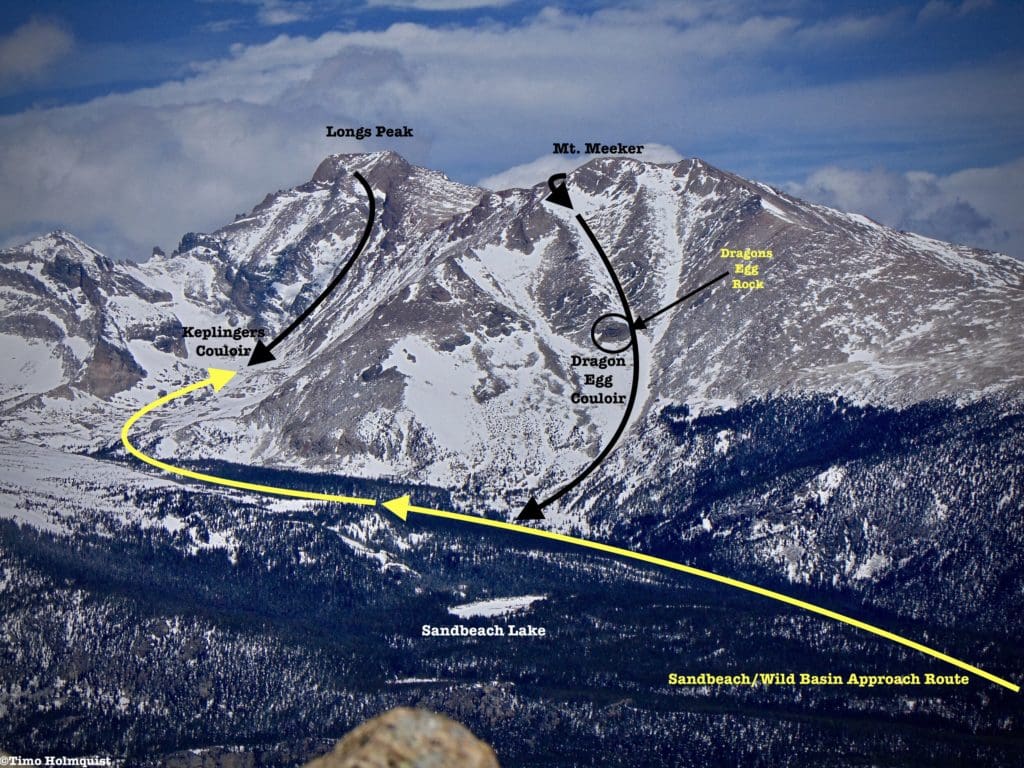

Map of Longs Peak South Area including Dragon’s Egg Couloir and Keplinger’s.

Longs Peak also has two gargantuan lines along its southern side. These lines are dangerous and long: requiring all-day outings to ascend and descend. They are approached via Wild Basin, which is south of the more popular East Longs Peak Trailhead. Appropriately named, Wild Basin is big and wild; if you don’t know the area well, don’t go.

If approaching from the south, look for a Wild Basin sign (brown) on the left side of US 7, just north of Allenspark. If approaching from the North, look for the sign on your right-hand side before getting to Allenspark. Once you drive past the National Park booths, you’ll see the parking lot on your right-hand side. In the summer, this is the trailhead for Sandbeach Lake. You’ll be following the summer route for the first couple of miles. Once you venture beyond Hunters Creek backcountry campsite, the route takes you into the Hunters Creek drainage; it will be the second major drainage you cross (the first one being Campers Creek). Instead of crossing the creek to its western side, follow the drainage uphill as it begins to veer north. You’ll follow the creek uphill for quite some time until the foliage opens up. During this section, you’ll see the massive hulk of Mount Meeker through the trees in front of you. When the drainage opens up and begins angling west, turn north and survey the scene. Leaving treeline, you’ll begin climbing up the large couloir in front of you. From this position, Meeker looks like a giant armchair, and you are climbing up the inset middle section, avoiding the ridges to either side. About halfway up, the couloir breaks into two strands, do not take the farthest right option; you’ll want to keep a north-north-west trajectory (just to the right of the namesake Dragon’s Egg rock) and climb up to just west of Meeker’s summit. From the summit ridge, strap in and turn around for a monster descent.

If your goal is Keplinger’s, instead of climbing up Dragon’s Egg couloir, continue following Hunter Creek drainage as it curves to the west. You’ll be in thinning trees for a while longer until they finally break. When they do, turn north and begin climbing up the base of Longs Peak. Scout the massive couloir, which will come down and intersect your path from the northeast (right). Once you’ve located the couloir, you have to climb it all the way up to just below the summit of Longs. In excellent conditions (rare), it is possible to ski from the summit. Keplinger’s does not come down from Meeker, instead, it gashes up in-between Longs and an unranked subpeak known as the Beaver. As you climb up you’ll notice the Beaver has a dramatic and cliffy north face called the Palisades, keep those cliffs to your right. Near the top, the couloir will abruptly turn from northeast to the northwest (sharp left) until intersecting the standard route up to the top of Longs. Enjoy the massive descent back down to treeline.

Photo of the Sandbeach/Wild Basin Approach Route including Dragon’s Egg and Keplinger’s Couloir from the south.

Dragon’s Egg Couloir

- Essentials: 1.3 miles, 3268-foot vertical

- Status: Very Difficult

- Steepest Slope Angle: 45 degrees

- Good for: Expert alpinists, mountaineers, and winter backcountry skiers. This is a long, hard to access and dangerous couloir. For the prepared and dedicated, its offer of over 3200 feet of descent is unrivaled in the area. Crampons, axe, avvy gear, and helmets are an absolute must. NOT for beginner/intermediate skiers.

- Accessed via: Sandbeach approach ascent, ~4.63 miles and 2173 feet of climbing will get you to just the bottom of the couloir. A bottom-up approach is preferable unless car positioning and already in possession of extensive regional knowledge. High avalanche risk mid-winter, melts out into sections by early July after a great winter or late May in below-average winters. Mount Meeker, because of its more easterly position, tends to melt out before Longs Peak. The ideal spring window for this line is April.

Keplinger’s Couloir

Photo looking up to the top of Longs and the homestretch from the side of Keplinger’s.

Photo looking up to the top of Longs and the homestretch from the side of Keplinger’s. Photo by Timo Holmquist.

- Essentials: 0.97 miles, 2,425-foot vertical

- Status: Very Difficult

- Steepest Slope Angle: 47 degrees

- Good for: Expert alpinists, mountaineers, and winter backcountry skiers. Like Dragon’s Egg, Keplinger’s is fast, fun, and FAR from help of any kind. Crampons, axe, avvy gear, and helmets are MANDATORY. NOT for beginners or intermediate skiers.

- Accessed via: Sandbeach approach ascent, up the valley from Dragon’s Egg. ~6.19 miles and 3233 feet of climbing will deposit you at the bottom of the couloir. High avalanche risk, not recommended for mid-winter unless snowpack is supremely stable. Keplinger’s tends to hold snow longer than Dragons Egg, usually through mid-June after good winters. It is possible to ski this line from the top of Longs in great conditions.

Lower Variation: Go as high as you feel comfortable, strap in and turn around. This variation allows you to avoid the variable, and cliffy areas around the Homestretch and the ledges above the start of the couloir. This is still a monster descent, go at a comfortable pace. With the right snowpack, you can ski all the way back to the Sandbeach approach trail.

At A Glance: ~6.7 miles, 3850-feet (combined with ascent route)

Steepest Slope angle: User discretion, can keep it in the mid-30s.

Photo looking down from the top of Keplinger’s, Palisade Cliffs on the left and wild basin beyond and thousands of feet lower.

Quick Terminology Reference Guide

-

Apron: An open section of a ski line, shaped roughly like an apron. It is generally shallower at the top, wider at the bottom.

-

Bootpack: A way to gain elevation utilizing the tough exterior of ski boots, literally creating steps in the slope with your ski boots. Only effective in mid-winter conditions with softer snow. Once ice forms, crampons, and an axe are best.

-

Bergschrund: Unlike a crevasse, which tends to form in the middle of a glacier, a bergschrund, or “schrund” for short is a crack or separation that forms between the top of a glacier and the mountain slope or stagnant snow behind it.

-

Chute: An inset area along a ridge that can hold great snow and presents like a natural ski run.

-

Cornice: An overhung area of snow that typically forms at the crest of a ridge or cirque. While the corniced ice and snow looks compact, there is usually nothing holding it up underneath; your weight alone can collapse a cornice. A collapsed cornice may also lead to avalanches. Do not stand on the edge of a cornice or climb up directly beneath one.

-

Couloir: Originally a French alpinist term, a couloir is a thin skiable chute. They are typically a no-fall zone and challenging to ski effectively.

-

Crevasse: A large crack that usually forms on glaciers during warmer times of year as the compact ice shifts. Very dangerous if fallen into.

-

Crown: The vertical fracture line that appears after a slab avalanche, indicative of unstable terrain.

-

Crux: Typically, the most dangerous section of an ascent or descent. Difficult routes can have multiple cruxes. A NO FALL ZONE.

-

Glade: A treed area of a particular slope or line.

-

Headwall: A topographical term used to mark where a basin, gorge, or alpine valley ends. Headwalls are usually steep and can sport multiple couloir options.

-

Line: The chosen path of skiers and snowboarders.

-

Pillows: Created when deep snow buries boulders, super fun to bounce between.

-

Runout: The bottom of a ski line, especially after a thin section or couloir, where the slope opens up. Similar to an apron.

-

Skin track: The route you use to ascend a slope, very important for backcountry navigation.

-

Terrain Trap: An area where snow from an avalanche can collect and bury a victim. More broadly, it is an area that it is difficult to ski out of once entered.

-

Wind-Slab: An area of compacted snow: formed by gusty winds. If near a steep slope, they can collapse and cause avalanches. Wind-slabs are often called wind-loaded slopes as well.

Final Thoughts

Longs Peak and the area around it support some of the biggest and baddest ski lines in the whole National Park. Many of these routes are for ski mountaineering and are not to be taken lightly. However, if extreme isn’t your game, the intermediate spread of lines around Battle Mountain keeps the options flowing for those looking to gradually improve their ski game. Whatever your fancy, Longs Peak should have a couple of interesting options for you, all with the added benefit of skiing near or down, the tallest peak in Rocky Mountain National Park. Please recreate responsibly and have fun!

Additional Resources:

AIARE, Avalanche Research Education. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://avtraining.org/

Colorado Avalanche Information Center. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://www.avalanche.state.co.us/

ClimbingLife. (2008). Lambslide Couloir. Retrieved from (http://climbinglife.com/lambslide-couloir/

Kelly, Mark. (2013). Backcountry Skiing and Ski Mountaineering in Rocky Mountain National Park. Giturdun Publishing Ltd.

Mountain Forecast (n.d.)

- Longs Peak. Retrieved from https://www.mountain-forecast.com/peaks/Hallett-Peak/forecasts/3875

- Mount Meeker. Retrieved from https://www.mountain-forecast.com/peaks/Mount-Meeker/forecasts/4240

- Storm Peak. Retrieved from https://www.mountain-forecast.com/peaks/Storm-Peak/forecasts/4062

National Park Service. (2020). Visitation Numbers. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/visitation-numbers.htm

- Rocky Mountain National Park. (n.d.) Fees and Passes. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/romo/planyourvisit/fees.htm

- Rocky Mountain National Park. (n.d.) Park Roads. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/romo/planyourvisit/road_status.htm

- Rocky Mountain National Park. (n.d.) Shuttle Bus Routes. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/romo/planyourvisit/shuttle_bus_route.htm

National Weather Service

- Estes Park Extended Forecast. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://forecast.weather.gov/MapClick.php?lat=40.3772059&lon=-105.5216651&site=all&smap=1&searchresult=Estes%20Park%2C%20CO%2C%20USA#.YCbnzxNKjOS

- Alpine Center/Trail Ridge Extended Forecast. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://forecast.weather.gov/MapClick.php?lon=-105.76022675170898&lat=40.42810400402635#.YCboWRNKjOS

Outside Online. (Nov. 3, 2017). The Backcountry Skiers Dictionary. Retrieved fromhttps://www.outsideonline.com/2257716/adventure-backcountry-skiers-dictionary

Powder Project (n.d.)

- Kilgore, Jason. North Face of Longs Peak. Retrieved from https://www.powderproject.com/trail/7000620/north-face-of-longs-peak

- Winey, Jacob. Keplinger’s Couloir. Retrieved from https://www.powderproject.com/trail/7000652/keplingers-couloir

- Rocky Mountain National Park Trails.com. (n.d.) Chasm Lake. Retrieved from http://www.rockymountainhikingtrails.com/chasm-lake.htm

- Rocky Mountain National Park Trails.com. (n.d.) Eugenia Mine. Retrieved from http://www.rockymountainhikingtrails.com/eugenia-mine.htm

- USDA: Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Water and Climate Center. (n.d.) Snotel Interactive Map.

- VisitEstesPark.com. (2021). Lodging. Retrieved from https://www.visitestespark.com/lodging/

Terms of Use:

As with each guide published on SKYBLUEOVERLAND.com, should you choose to go backcountry skiing, do so at your own risk. Prior to setting out check current local weather, conditions, and land/road closures. While taking a trail, obey all public and private land use restrictions and rules, carry proper safety and navigational equipment, and of course, follow the #leavenotrace guidelines. The information found herein is simply a planning resource to be used as a point of inspiration in conjunction with your own due-diligence. In spite of the fact that this guide was prepared under diligent research by the specified contributor and/or contributors, the accuracy of such and judgement of the author is not guaranteed. SKYBLUE OVERLAND LLC, its partners, associates, and contributors are in no way liable for personal injury, damage to personal property, or any other such situation that might happen to individuals following this guide.

Popular Articles:

Adventurer’s Guide To Rocky Mountain National Park

Best Hiking Trails in Rocky Mountain National Park

Backcountry Skiing in Rocky Mountain National Park: Bear Lake Area