|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

If you’re like me and winter represents a chance to embrace powdery glory at a resort or in the vast reaches of the backcountry, it helps to understand the very basics of how and when wintry weather affects the centennial state.

Ah, Colorado, the roof of the southern Rockies, eternal outdoor playground, and home to many famous ski resorts. If you’re like me and winter represents a chance to embrace powdery glory at a resort or in the vast reaches of the backcountry, it helps to understand the very basics of how and when wintry weather affects the centennial state. Perhaps predictably, it has a lot more to do with geography, wind, moisture, and global climate patterns than county and state lines. After we explore all the factors that need to come together to make a successful Colorado winter, we’ll wrap up by talking about long-term trends and what to expect in the future.

Fresh backcountry turns on the western slope.

Support Skyblue Overland™ on Patreon!

If you’d like to support our efforts for a few dollars a month, please subscribe to our Patreon page. Every donation energizes our team to keep writing detailed trail reviews, gear reviews and adventure guides. Thank you!

Table of Contents:

Article Navigation: Click on any of the listed items in the table of contents below to jump to that section of the article. Similarly, clicking on any large, white section header will jump you back to the Table of Contents.

- The Big Picture

- Early Season favorites

- Favorable Winds

- The Jet Stream

- Front Range

- Future, Now

- What Does it All Mean?

- Key Points to Remember about Colorado Winters

- Resources

The Big Picture

Snow arrives in Colorado in a few different ways. Compared to the amounts deposited along the Pacific Coast during an atmospheric river, totals in the state per individual storm can seem a little anemic (still, we’re talking up to feet of snow in either scenario), but the snow quality has long been billed as the distinguishing factor. Colorado snow is lighter, drier, and while less of it may fall (when compared to some of the Cascades or Sierra), when it does, the chances of finding blower powder are higher.

The reason Colorado snow is drier is that it’s far from an ocean, i.e., an essential deposit of moisture. By the time storms reach Colorado, they are usually a little parched, which means the snow that falls is lighter (less water content) and easier to move through. It also means, because of Colorado’s distance from oceans, there isn’t one overarching climate pattern we can point to that can accurately predict how fierce or tame a Colorado winter will be, additional factors need to play in our favor in order to produce big storms.

Now, just because there isn’t one easy answer to Colorado’s winters doesn’t mean there aren’t some important weather factors involved. In order to produce snow, we need moisture, and looking at a map, we can see that Colorado is right in the middle of a lot of continent. Prevailing winds in the region take a west to east approach, which means despite the distance to it, the Pacific Ocean is our primary weather maker.

Blue sky moments at Loveland Ski Area.

The Pacific Ocean is enormous and can be split into a northern and southern half. Both halves are affected by an oscillation between warm and cold ocean temperatures. The northern oscillation is called the PDO (Pacific Decadal Oscillation), and the southern oscillation is called ENSO (El Nino Southern Oscillation). Basically, when the waters in the middle of the Pacific Ocean are warmer, weather in the US behaves differently than when those waters are colder. To explore each’s influence on weather in the centennial state, check out this article by Joel Gratz of Opensnow. In short, because Colorado is far from big water, individual winters are hard to predict.

What has become easier to predict is the slow decline of Colorado’s overall snowpack. This is bad for many reasons, including loss of recreation and a lower water supply for millions of people. To really dive into the specifics, check out this fantastic article by Matt Makens of Weather5280. It’s a great read (scary if you’re worried about snowpack over time) and comments on all things snow for Colorado up until ~2017.

May 30, 2015 in the San Juan alpine with a ton of snow leftover from a productive spring.

So, before we explore the intricacies of when and where Colorado gets snow, let’s operate under a few general points.

- Colorado long-range forecasts (3-6 months out) are seldom accurate.

- Colorado’s overall mountain snowpack is slowly declining.

- The snowpack decline is not uniform because snow does not fall uniformly across the state.

- There are large seasonal variations in snowfall rates that can still produce blockbuster snow totals for certain locations.

- Weather generally moves through the state from west to east (with notable exceptions).

- Colorado snowpack is affected by the PDO and ENSO cycles. The relationship is complicated.

- When it snows, Colorado has lighter snow, and individual storms produce anywhere from a few inches to around 3 feet per storm.

- Generally, the ranges closer to the Pacific Ocean collect snow more consistently (Mt. Baker in the Northern Cascades collects ~651 inches per year, while Colorado’s top resort Wolf Creek, hauls in a season average of 430), but it’s tougher snow to ski through.

- While the highest chance for storms producing multiple feet of snow goes to the West Coast, Colorado can still throw down some impressive storm totals, including a 24-hour snowfall record of 75.8 inches (6.3 ft.) in Silver Lake, Colorado. We’ll discuss why that happened in the Front Range section below.

The silver lining is Colorado gets less snow than other areas of the west, but the snow is lighter and fluffier. The season totals for most Colorado resorts averages around 300 inches, with mountain extremes in the northern Park Range (~500 inches avg.) and occasionally the San Juan’s.

Early Season Favorites

People have long said that it can snow at any time of year in Colorado, and that’s true. I worked for the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative building trail on 14,000-foot mountains and saw quite a few examples of summer snow.

Snow on sunlight & Windom from pk. 11. August 24, 2016, San Juans.

However, a summer snow spritz and accumulating snow are different. Most of the high peaks tend to see accumulating snow return from mid-September to mid-October. The snow level gradually works its way down until most mountain locations are capable of seeing snowflakes by thanksgiving. Obviously, having a favorable temperature isn’t a guarantee that it will snow. In fact, there are places that see snow a lot earlier in the season than others despite similarities in elevation or aspect. Ok, why?

Well, snow comes in from the Pacific, which is west of Colorado. Most of Colorado’s weather crosses the state from west to east (with variations). Very, very simply, the western slope tends to fill out first. Naturally, there are caveats.

The first ski resort in the state to open is usually Arapahoe Basin, which not only has a lower average snowpack than other ski resorts in the state but is also more east than many western slope resorts. So, what gives? Geography, elevation, and timing.

Early season conditions in A-Basin’s Montezuma Bowl.

Arapahoe Basin benefits from early season storms because the base elevation for the resort is high. As long as snow is falling at an elevation of 10,700 feet or higher, A-Basin will collect. A-Basin also sits in a recessed basin along the Continental Divide, which shields a lot of its north-facing terrain from the sun. The takeaway is that A-Basin’s advantage in geography, elevation, and slope aspect, means it can spin up at least one lift in October almost every year. Similarly, A-Basin can benefit from late-season storms. So, while it may be raining in Denver, you could be skiing a powder day as late as June 23 at A-Basin, shown in the pic below. That year, A-Basin stayed open until July 4th.

Powder day June 23, 2019.

Now, A-Basins advantage isn’t as apparent when the temperatures are cold enough to produce snow across a wide swath of terrain. If the terrain west of A-Basin is cold enough, it will generally see the larger totals before storms get to A-Basin. Yes, A-Basin has the longest average season of any resort out west; no, it’s not because they always get the largest dumps of snow (although they can still get clobbered—see The Favorable Wind section below). A-Basin collects snow far outside the normal ski season (Nov-April) and does a better job of holding onto that snow with high elevation terrain sheltered from long periods of sunlight.

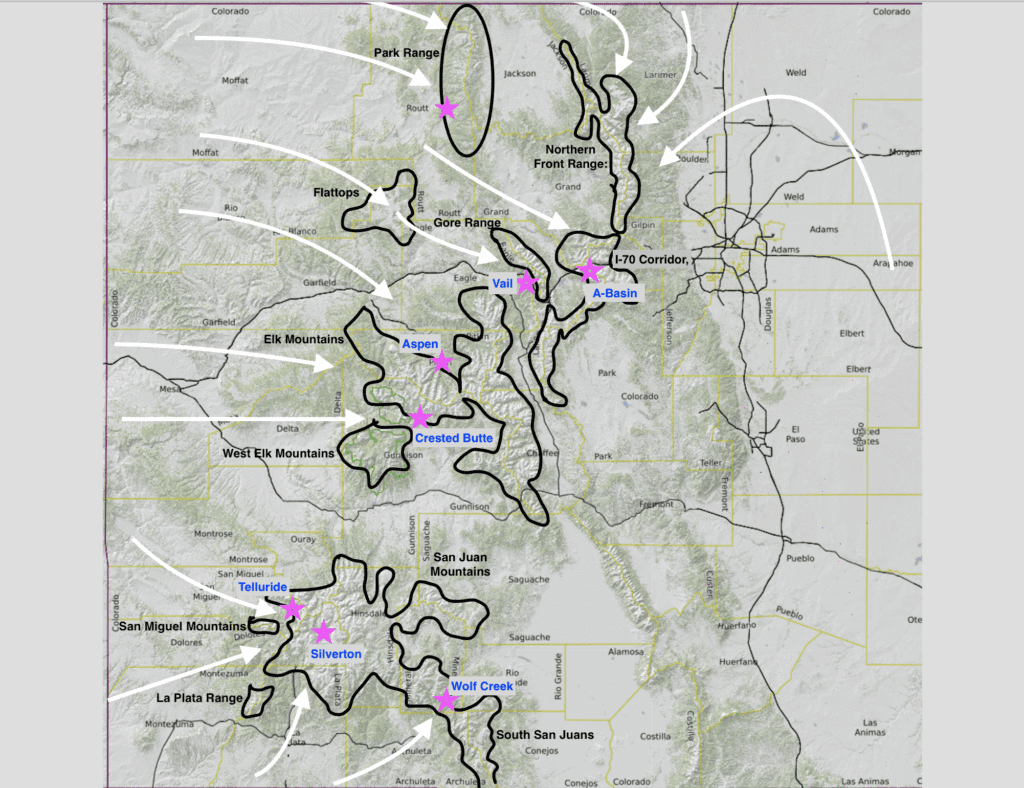

Aside from these late autumn collection zones (A-Basin, Loveland, Wolf Creek, Silverton, and occasionally Keystone), the first part of the winter favors the western slope. Once winter weather makes its way to the state, the first ranges it encounters are usually the Flattops, Park Range, Gore Range, Elk Mountains, and San Juan’s. Areas that can benefit from early winter snowfall include Aspen, Telluride, Silverton, Wolf Creek, Steamboat, Vail, and occasionally Crested Butte. Again, that’s a general statement and depends on other weather factors and wind direction.

Making turns on a thin November snowpack.

Favorable Winds

Wind is one of the defining factors regarding what mountains get accumulation. Every resort has a “favorable” wind direction. What does that mean? Well, mountains produce snow in Colorado via a process called orographic lift. According to NOAA, orographic lift “occurs when air is forced to rise and cool due to terrain features such as hills or mountains. If the cooling is sufficient, water vapor condenses into clouds. Additional cooling results in rain or snow.” That means there are certain paths the wind can take to get to Colorado from the Pacific Ocean. Depending on the wind’s specific path, some ski resorts will get more snow than others.

Favorable wind direction=White Arrows, Stars=ski resorts, Black outlines show areas of high elevation i.e. where orographic lift is likely to occur.

Looking at the wind map above, you can see why certain resorts have favorable wind. Since orographic lift only occurs when air is forced to rise, the first high-elevation slopes that force the wind to rise will generally squeeze the most precipitation out of the sky. The “favorable” wind is the direction with the least amount of geographic resistance prior to arriving at a ski area. Translation: if a NW wind whips into Vail, the only thing it’ll have to clear on the way in is the Flattops, and because there’s less for the wind to get around, there’s a better chance it will drop more snow near the resort. A wind from the southwest, for example, would have to travel over a lot of mountainous terrain to get to Vail. Vail can still get a respectable amount of snow out of a strong southwestern storm, but it won’t be as much as some areas in the San Juan’s that are on that leading orographic edge.

If you’re wondering whether that means snowfall rates differ across the state, the answer is yes. Let’s take the orographic lift concept and expand it to include the whole west. Can you see which two ranges have the easiest path to tapping into that Pacific moisture?

Western winds.

As we talked about before, it’s generally harder for Pacific moisture to find itself in Colorado, but if you look at my awful drawing of the Cascades, you’ll notice large gaps between the volcanos where storms and moisture can pass relatively easily. A storm and wind track through the Columbia River Basin, into the Snake River Basin, and through SW Idaho minimizes orographic interference until slamming gleefully into the Park Range near Steamboat Springs. The San Juan’s also have a relatively easy path to moisture from the southwest, with the only significant interference being the Mogollon Rim in Arizona and New Mexico.

Additional Factor: The Jet Stream

Separate from prevailing westerly winds, the jet stream is a funnel of fast air that whips around the world in the upper atmosphere. When a combination of the jet stream and ample moisture occurs over Colorado, we can get some fantastic snowstorms. They can also be dangerous. Just because Colorado doesn’t have the snowpack of the Cascades doesn’t mean it can’t get nasty up there.

Storm skiing in the Stone Creek Chutes of Beaver Creek Ski Resort.

You may have heard a lot of talk about El Niño and La Niña as well. Collectively, they are known as the El-Niño Southern Oscillation, which has to do with global above-surface winds. During La Niña years (when strong trade winds push warm water towards Asia), a strong polar jet stream takes shape over the pacific northwest. This can benefit many states to our northwest and occasionally the northern third of Colorado.

El Niño (when trade winds are weak, pushing warmer water towards the U.S.) can result in a particularly active southern jet stream that pumps up precipitation totals for the southern parts of the state while leaving the northern part drier. Colorado, unfortunately, isn’t in the crosshairs of either situation, so seasonal variability can be expected. The jet stream moves kind of like a whip, bending both up and down as it encounters different competing natural forces. Sometimes, the bend passes through the state along with the arrival of moisture and delivers the goods; sometimes, the stream bends too far north or south and misses us completely. Its dynamic flow is pretty critical to understanding how it can help or hinder; here’s a nice visual, and here’s a great video explanation of what jet streams do globally (yup, there’s more than one).

Sneaky cornices forming in early December.

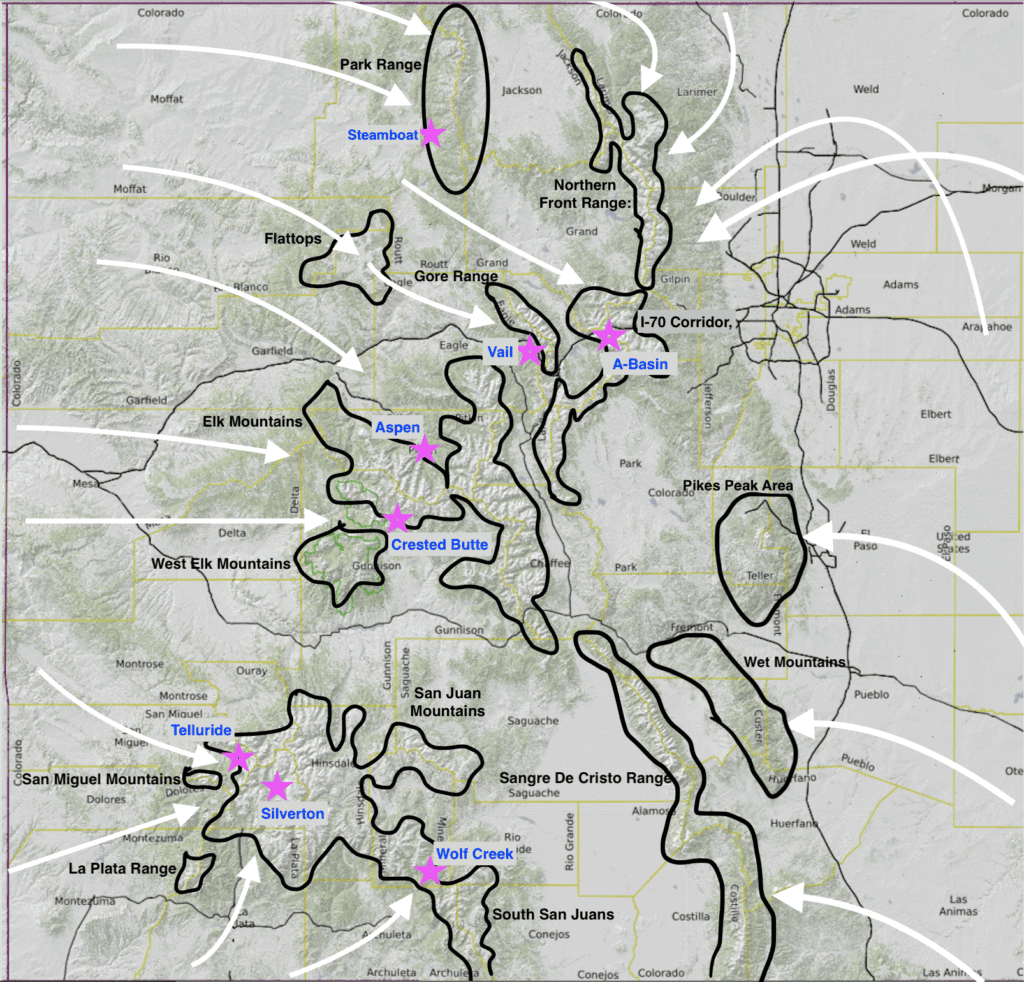

When the jet stream bends into the state, the wind gets REALLY strong. A lot of the Front Range is susceptible to wind stripping, which occurs when the wind picks up and tosses snow to a different location, leaving eastern and southern slope aspects bare. A great example is the eastern flank of Mt. Meeker, which is highly visible from Denver north to Fort Collins and barely gets covered with snow despite rising to more than 13,700 feet. The exceptions are recessed couloirs and protected faces that make up the bulk of Front Range backcountry skiing. That wind, while responsible for stripping a lot of the Front Range snow, is also a key ingredient for the mighty upslope storm.

The Front Range

Sitting farther east than all major ranges in the state, the Front Range is usually the last to see the white stuff. Exceptions can be made for the far northern part of the range (less orographic resistance if the wind comes in from the northwest) and occasionally the southeastern mountains (the Wet Mountains can pull in a respectable amount of precip. if storm ingredients are right). Just because the general weather pattern is west to east doesn’t mean the Front Range doesn’t collect, though. It just collects a little later. Denver’s best snow chances, for example, occur in March (avg. 11.8 inches) and are heightened throughout April (8.8 inches). The average height of the snowpack for the South Platte River Water Basin (which includes most of the Front Range north of Palmer Divide) peaks around April 25, and you can be sliding around on large connected snow patches in the alpine through June.

Map of Upslope wind and affected areas

If you look at the map above, you’ll notice that there is a favorable wind direction for the Front Range. This is called wraparound or upslope wind. Essentially, an area of low-pressure parks itself in SE Colorado and rotates; the circulation comes in counter-clockwise, pulling precipitation in from the Gulf of Mexico and throwing it into the Front Range. These types of storms are not guaranteed but do occur with some regularity (every 1-5ish years), contributing to the later peak snowpack numbers for the region. Additionally, these storms can be monsters, dropping up to a still-standing 24-hour snowfall record of 76.8 inches in Silver Lake, Colorado, way back in 1921. A lot of factors have to combine to set the conditions for an Upslope storm, but they can wreak havoc on the eastern slope of the Front Range all the way down to the cities. All of Denver’s ten biggest blizzards have been due to upslope conditions, including the upslope storm in March 2021.

The Northern Front Range after an Upslope Storm.

Future, Now

Based on historical data, Colorado is losing snow. As I’ve indicated before, there are wild seasonal fluctuations that favor certain mountains over others, but the long, linear trend for statewide snowpack is that it’s going down. You can revisit some of that data here and here. Autumn is lasting longer, and summer appears to be starting quicker. So, is there any hope for winter? Yes and no.

Vail Pass, elevation ~10,665 ft., after a late April snowstorm.

Winter in Colorado isn’t going to shut off, but I think it’s going to become more erratic. Some years we’ll shatter snowfall records (‘18/’19), and others, we’ll fall hopelessly short of average (‘12/’13). So, knowing that we have a slowly declining snowpack and wildly variable winters, timing is going to matter more and more regarding when we can ski the best conditions. The key ingredients to future powder skiing are going to be timing, flexibility, a backcountry skill set, and/or a season pass at a high elevation resort.

Fresh backcountry tracks during the last week of April.

Simply put, the Colorado snowpack won’t look the same in a few decades. If you live in Colorado, that’s not immediately awful news, but it does mean understanding that some winters are going to be better than others. For the state’s drought levels and wildfire concerns, lower snowpack will lead to an increase in both. Slowly, Colorado and the west at large are drying out.

Looking down into summer, May, 2021, Rocky Mountain National Park.

What does it all mean?

Well, as always, that depends on who you’re asking. From a vacation planning standpoint, the Christmas/New Year’s timeframe can be very feast or famine. The best vacations to plan a Colorado ski trip around are MLK or Presidents Day. From a weekend warrior standpoint, try your hardest to avoid I-70 on Friday afternoons and Sundays. And from a Front Range weather standpoint, keep an eye on March and April; the area can get hit with big springtime storms.

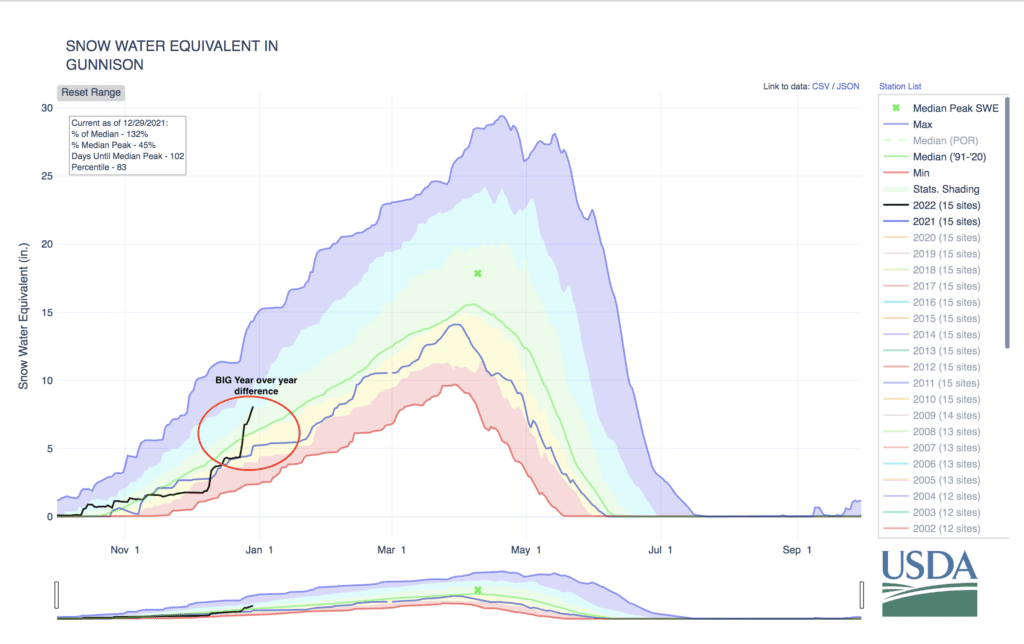

If you’re chasing resort powder throughout the season, start with A-Basin, Loveland, Silverton, and Wolf Creek because of their geographic advantages. From November-March, the western slope fills out faster and often deeper with big totals for individual storms (Vail, Aspen, Steamboat, Crested Butte, Wolf Creek, Telluride, and occasionally Beaver Creek). It will not fill in evenly, some areas get skunked, and it always depends on favorable winds. A great example of this is Crested Butte. As I’m writing, they’ve received more than 100 inches of snow in a two-week period, which is awesome! Last year, however, the Gunnison River Basin snowpack (where Crested Butte is located) hovered below average for the entire winter. One great season does not a pattern make. Use other factors like historical averages, recent weather reports, ease of access, accommodations, road conditions, etc. before committing to a resort.

Gunnison River Basin snowpack totals and averages. Look at the black and blue lines to compare 20/21 and 21/22 winters so far. Map courtesy of USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service Colorado.

As springtime creeps back in, high elevation begins to matter again so the I-70 corridor from Loveland to Copper can pull snow out of the atmosphere while lower elevations may be raining. Caveats to the above include powerful upslope storms that make spring a fun time to explore the Front Range backcountry or resorts like Eldora.

Fresh snow after an Upslope storm.

If you ski in the far southern part of the state (Wolf Creek, Silverton, Purgatory, Telluride), you can get an additional advantage out of an El Niño year, which tends to dump snow on the Mogollon Rim, the San Juan’s, and the Sangres of New Mexico (Taos/Ski Santa Fe). If you ski in the far northern part of the state (Steamboat, Cameron Pass, RMNP, Bluebird Backcountry, Park Range, or into the Medicine Bow), a La Niña wind pattern can benefit you. Unfortunately, with both patterns just clipping the state, the I-70 corridor and central mountains don’t usually get a huge bump from this.

If you’re into backcountry skiing but not into avalanches, resort ski through the season and then take it to the high country in April. The peak snowpack for Colorado doesn’t usually occur until late April, yet many ski resorts (Aspen, Vail, Steamboat, Telluride, etc.) close before that because they have lower base elevations. The few exceptions are Loveland, A-Basin, Breckenridge, and Winter Park, which are spring skiing meccas. Even though resorts have thousands of acres of terrain, the offerings are going to be more and more limited as the snowpack continues declining. Taking advantage of the backcountry is probably the best way to chase powder long-term but also comes with wildly heightened risk across the board. Make sure you understand backcountry gear and all the planning involved with any backcountry adventure before attempting one.

Beautiful spring conditions in the Cameron Pass area.

Key points to remember about Colorado Winters

- One state, many winters.

- Weather generally comes into the state from W. to E. with N. S. variations. The western slope usually sees snow first.

- Colorado is far from its primary weather maker (the Pacific Ocean), so storms are less frequent than coastal mountain ranges, however, the snow quality is much higher.

- Colorado ski resorts average around 300 inches per year with Loveland, Wolf Creek and Silverton all averaging near or over 400.

- Colorado’s high elevations mean accumulating snow can occur as early as September and can last until June.

- High elevation, early season storms help a few key resorts open terrain first (Wolf Creek, A-Basin, Loveland, Silverton).

- The snowiest mountain range in the state is the Park Range N. NE of Steamboat.

- The San Juan’s are a bit bipolar. Some years are thin but on good years, snowpack totals can often match or exceed Park Range totals.

- Your favorite resort has a favorable wind direction, more often than not, when a storm takes the favorable track, it can translate to deep powder.

- La Niña and El Niño can help deliver snow but their influence is less than it may seem because a lot of the state falls between each’s influence on the jet stream.

- The Front Range doesn’t start collecting snow first, though it often melts last (evidenced by a series of alpine glaciers on the leeward side of the Divide between the IPW and RMNP).

- In the event of an upslope storm, the Front Range and east to the foothills can be favored for feet of accumulation (more in the deeper basins tucked into the Continental Divide). Big upslope storms occur roughly every 1-5 years.

- Colorado’s overall snowpack is slowly declining.

- If you’re heading into the backcountry, be aware that the western slope acts MUCH differently than the Front Range. Backcountry skiing in the Front Range is best in recessed basins, alpine couloirs and sheltered slopes where wind stripping occurs less.

- NEVER go into the backcountry unprepared, use CAIC (Colorado Avalanche Information Center) for updated information. We STRONGLY recommend getting an avalanche certification and the appropriate gear.

Winter in the Gore Range.

Additional Resources

Open snow and Weather 5280 are fantastic resources for all things weather in the centennial state.

Onthesnow. (2021, June 14). How the mountains of Colorado make natural snow. Onthesnow. Retrieved from https://www.onthesnow.com/news/how-the-mountains-of-colorado-make-snow/

East, M. (2020, Nov. 2). What is Upslope Snow and how does it form? Spectrum News 1. Retrieved from https://spectrumlocalnews.com/nc/charlotte/blog/2020/11/02/what-exactly-is-upslope-snow-

Makens, Matt. (2017, Nov. 29). Perspectives on Colorado’s Snowpack: Is There A Downward Trend?Weather 5280. Retrieved from https://www.weather5280.com/blog/2017/11/29/perspective-on-colorados-snowpack-is-there-a-downward-trend

Pielke, R. et. al (2001) Colorado Climate Winter 2001-2002. Colorado State University. Retrieved from http://climate.atmos.colostate.edu/pdfs/winter2001.pdf

Reeser, Shawn. (2021, Oct. 11). How much does it snow in Colorado? Uncover Colorado. Retrieved from https://www.uncovercolorado.com/how-much-does-it-snow-in-colorado/

NOAA (2021, June 4). What are El Nino and La Nina? National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ninonina.html

Nelson, Mike. (2021, March 10). Upslopes vs. downslopes: The Colorado Weather Phenomenon, explained. Denver 7. Retrieved from https://www.thedenverchannel.com/weather/weather-news/upslopes-vs-downslopes-the-colorado-weather-phenomenon-explained

Berman, Samantha. (2021, March 15). It Snowed So Much in Colorado, Skiers Couldn’t Get To The Mountains. Outside. Retrieved from https://www.skimag.com/news/it-snowed-so-much-in-colorado-skiers-couldnt-get-to-the-mountains/

Gratz, Joel. (2017, Jan. 4). Favorable Weather Patterns for Vail. Vail. Retrieved from http://blog.vail.com/favorable-weather-patterns-vail/

Gratz, Joel. (2016, Aug. 22). How El Nino, La Nina and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation influence snowfall in the United States. Unfortunately, it’s complicated. Opensnow. Retrieved from https://opensnow.com/news/post/how-el-nino-la-nina-and-the-pacific-decadal-oscillation-influence-snowfall-in-the-united-states-unfortunately-it-s-complicated

Sebastian, Matt. (2021, March 9). Denver weather: The Mile High City’s 10 largest snowstorms on record. Denver Post. Retrieved from https://www.denverpost.com/2021/03/09/denver-weather-largest-snowstorms/

Gesing, Lars. (2019, Jan. 24). Four seasons: Colorado water in a changing climate. Colorado Independent. Retrieved from https://www.coloradoindependent.com/2019/01/24/colorado-snowpack-climate-change/

Heberton, Brendan. (2021, March 15). Blizzard of March 2021 will stand as the 4th biggest snowfall on record for Denver, final update and snowfall totals. Weather 5280. Retrieved from https://www.weather5280.com/2021/03/15/blizzard-of-march-2021-will-stand-as-4th-biggest-snowfall-on-record-for-denver-final-update-and-snowfall-totals

NRCS. (n.d.) Snow water equivalent in South Platte. USDA. Retrieved from https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/WCIS/AWS_PLOTS/basinCharts/POR/WTEQ/assocHUCco_8/south_platte.html

NASA Scientific Visualization Studio. (2016, Dec. 11). The Polar Jet Stream. NASA. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m0TuC34WSR8

Met Office – Learn About Weather. (2018, May 29). What is the jet stream and how does it affect the weather? Met Office. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lg91eowtfbw